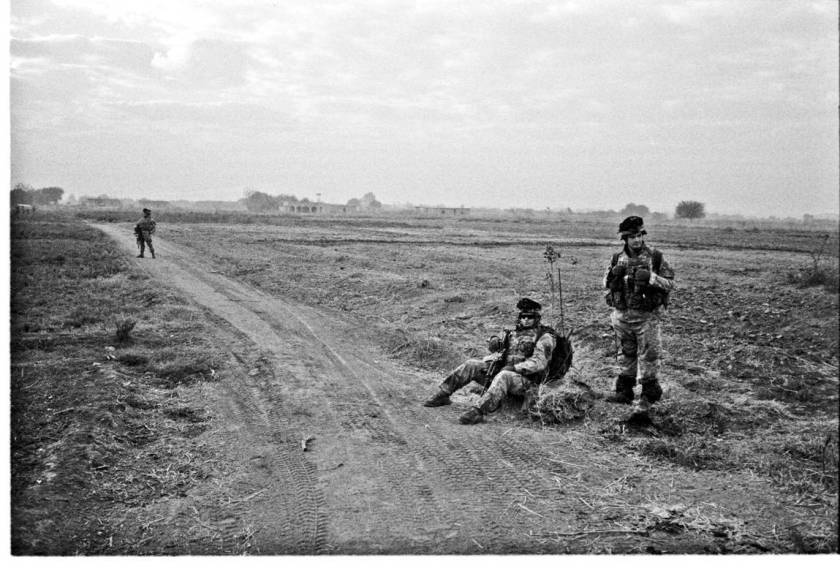

In previous posts I have discussed three poets — Walter E. Piatt, Paul Wasserman, and Elyse Fenton — who explore how the contemporary wars have wrought alterations of perspective and emotion on those who fight them and those who have been affected by them. Below I offer a few comments on Brian Turner, by far the most well-known and important of contemporary war poets.

The author of two volumes of verse, Here, Bullet (2005) and Phantom Noise (2010), Turner combines an MFA in creative writing from the University of Oregon with seven years of service as an enlisted infantryman, to include a tour in Iraq with the 2nd Infantry Division. As such, he sits astride the domains of both the academic poetry establishment and the hundreds and thousands of veterans who have used verse to articulate their war experiences. Neither entirely in one camp nor the other, he complicates assumptions and expectations of each by being at once sensational and subtle, raw and refined, accessible and complex. A good example is the title poem of his first volume:

"Here, Bullet"

If a body is what you want,

then here is bone and gristle and flesh.

Here is the clavicle-snapped wish,

the aorta's opened valves, the leap

thought makes at the synaptic gap.

Here is the adrenaline rush you crave,

that inexorable flight, that insane puncture

into heat and blood. And I dare you to finish

what you've started. Because here, Bullet,

here is where I complete the word you bring

hissing through the air, here is where I moan

the barrel's cold esophagus, triggering

my tongue's explosives for the rifling I have

inside of me, each twist of the round

spun deeper, because here, Bullet,

here is where the world ends, every time.

Interesting about the poem is the marriage of modern war imagery and emotion with the classical verse form of the apostrophe (a direct address to a non-human thing), all informed by a poetic smartness about half-rhymes, assonance, alliteration, and other literary effects. Thematically, the poem presents an original take on bravery. The poem is half-taunt and half-cry of pain, the challenge to the onrushing bullet a futile effort to both resist and understand war’s deadliness. The blur of emotions is matched by the interpenetration of the imagery, where the rifle and bullet are given human qualities and the soldier-speaker’s body parts are weaponized, as in “the barrel’s cold esophagus” and “my tongue’s explosives.”

The metaphysical musing of “Here, Bullet” is typical of many Turner’s poems, which only sometimes stop to consider events in which he personally participated. Occasionally though he works in a biographical vein. A great example is “Night in Blue,” from Here, Bullet. Several readers have told me it is their favorite Turner poem:

"Night in Blue"

At seven thousand feet and looking back, running lights

blacked out under the wings and America waiting,

a year of my life disappears at midnight,

the sky a deep viridian, the houselights below

small as match heads burned down to embers.

Has this year made me a better lover?

Will I understand something of hardship,

of loss, will a lover sense this

in my kiss or touch? What do I know

of redemption or sacrifice, what will I have

to say of the dead -- that it was worth it,

that any of it made sense?

I have no words to speak of war.

I never dug the graves of Talafar.

I never held the mother crying in Ramadi.

I never lifted my friend's body

when they carried him home.

I have only the shadows under the leaves

to take with me, the quiet of the desert,

the low fog of Balad,

orange groves with ice forming on the rinds of fruit.

I have a woman crying in my ear

late at night when the stars go dim,

moonlight and sand as a resonance

of the dust of bones, and nothing more.

When Turner isn’t considering his own emotions or the cosmological significance of war, his dominant mode is empathy for those with whom and against whom he fights. Two examples will suffice, one recording a birth in Iraq and one a death:

"Helping Her Breathe"

Subtract each sound. Subtract it all.

Lower the contrailed decibels of fighter jets

below the threshold of human hearing.

Lower the skylining helicopters down

to the subconscious and let them hover

like spiders over a film of water.

Silence the rifle reports. The hissing

bullets wandering like strays

through the old neighborhoods.

Let the dogs rest their muzzles

as the voices on telephone lines

pause to listen, as bats hanging

from their roosts pause to listen,

as all of Baghdad listens.

Dip the rag in the pail of water

and let it soak full. It cools exhaustion

when pressed lightly to her forehead.

In the slow beads of water sliding

down the skin of her temples --

the hush we have been waiting for.

She is giving birth in the middle of war --

the soft dome of a skull begins to crown

into our candlelit mystery. And when

the infant rises through quickening muscle

in a guided shudder, slick in the gore

of birth, vast distances are joined,

the brain's landscape equal to the stars.

"Eulogy"

It happens on a Monday, at 11:20 A.M.,

as tower guards eat sandwiches

and seagulls drift by on the Tigris River.

Prisoners tilt their heads to the west

though burlap sacks and duct tape blind them.

The sound reverberates down concertina coils

the way piano wire thrums when given slack.

And it happens like this, on a blue day of sun,

when Private Miller pulls the trigger

to take brass and fire into his mouth:

the sound lifts the birds up off the water,

a mongoose pauses under the orange trees,

and nothing can stop it now, no matter what

blur of motion surrounds him, no matter what voices

crackle over the radio in static confusion,

because if only for this moment the earth is stilled,

and Private Miller has found what low hush there is

down in the eucalyptus shade, there by the river.

PFC B. Miller

(1980-March 22, 2004)

Turner poems record such facts of modern war experience as IEDs, women in uniform, “enhanced interrogation techniques,” and PTSD, but the characteristic most worth mentioning in conclusion is his deep interest in history. Turner’s not particularly interested in politics and his sense of the war’s ethical dimensions is expressed obliquely. He is, however, ever conscious that the Iraq soil on which he fought had a long, richly-recorded existence before America turned it into a 21st century battleground. This pre-history of Operation Iraqi Freedom wells up in Turner’s poetry in the form of references to ancient texts, images of ghosts, evocations of ancestors, and readiness to consider contemporary events in a temporal context extending deep into the past and into the future.

"To Sand"

To sand go tracers and ball ammunition.

To sand the green smoke goes.

Each finned mortar, spinning in light.

Each star cluster, bursting above.

To sand go the skeletons of war, year by year.

To sand go reticles of the brain,

the minarets and steeple bells, brackish

sludge from the open sewers, trashfires,

the silent cowbirds resting

on the shoulders of a yak. To sand

each head of cabbage unravels its leaves

the way dreams burn in the oilfires of night.

Turner, the first or near-first Iraq veteran to turn his war experience into verse, has established an impressive standard of both poetic craft and thematic depth for the poets who have followed him. I highly encourage everyone to read Here, Bullet and Phantom Noise cover-to-cover to fully experience Turner’s stunningly imagined representation of how the war in Iraq was fought and how it was felt.

This post previously appeared in altered form on Thomas Ricks’ Foreign Policy blog The Best Defense.

Here, Bullet was published in 2005 by Alice James Books.

Phantom Noise was published in 2010 by Alice James Books.

Permission to quote Brian Turner’s poetry has been granted by Alice James Books: www.alicejamesbooks.org