As memories of ground combat in Iraq and Afghanistan fade into history, so too slows the pace of narratives that depict fighting men and women in post-9/11 combat action. From what I observe, the large American publishing houses have little interest in publishing novels about war in Iraq and Afghanistan, nor does there appear to be a mass reading audience clamoring for such fare. The big three vet-authors who have undeniably made it as professional writers—Phil Klay, Matt Gallagher, and Elliot Ackerman—are moving on to other subjects and writing identities not strictly identified with their formative years deployed on Operations Iraqi and Enduring Freedom. The same might be said of some of the vet-poets who were prominent a decade or so ago. A number of other vet-writers and affiliated civilian-authors in the war-making scene appear to have gone fallow or given up. New lights might shine for a season, but sustained achievement and acclaim await.

And yet… and yet….

On a smaller scale, fiction and poetry in which Iraq and Afghanistan figure, or serves as a backdrop, or as the genesis for the writing impulse keeps coming. Here’s to the authors, to the readers, and most of all to the publishing houses who keep war-and-mil writing alive. More than just alive, really, but expanding and developing. It’s not enough to tell an old story in an old way, and new perspectives and story-lines aplenty are on display in the titles I survey below.

Michael Anthony, with art by Chai Simone, Just Another Meat-Eating Dirtbag. Street Noise Books, 2022.

Anthony’s memoir Civilianized is one of the best traumatized-and-dysfunctional vet sagas going, and now his graphic-memoir Just Another Meat-Eating Dirtbag spins the story of his long journey back from war in unexpected and completely original directions. Finding love with a vegan animal rights activist, the title character, named Michael, grapples with his own ideas and beliefs about the subjects and discovers they are more deeply seated in his war experience than he cares to confront. Though packed with vegan and animal-rights polemics, Just Another Meat-Eating Dirtbag manages to avoid preachiness while also telling a very human story about strained relationships and the redemptive power of love.

Amber Adams, Becoming Ribbons. Unicorn Press, 2022.

Becoming Ribbons features several poems about Adams’ own deployment as an Army reservist, but the bulk of the poems relate the story of her long-term relationship with a Marine spouse. Looking back at high school and courtship, then exploring marriage in the midst of multiple deployments, moving on to her spouse’s wounding and rehabilitation, and then followed by divorce, her ex-husband’s suicide, and then her own new love, Becoming Ribbons covers a lot of narrative ground, even as each individual poem stands on its own as a unique, discreet verse. Adams’ poetry is deft and mature, while also being remarkably open about fraught events and vexed emotional responses.

M.C. Armstrong, American Delphi. Family of Lights Books, 2022.

Armstrong is not a vet, but he crafted a perceptive and finely-wrought memoir about a short-stint as a journalist with a Special Forces team in Iraq titled The Mysteries of Haditha. Now comes American Delphi, a Young Adult novel about a troubled adolescent girl and her troubled combat-veteran father. I haven’t read American Delphi yet, but as Time Now has regrettably not paid much attention to GWOT YA, I hope to soon. Bonus points for what American Delphi promises are futuristic tech-y elements and a trenchant engagement with social-media-based political activism.

Randy Brown, Twelve O’Clock Haiku: Leadership Lessons from Old War Movies and New Poems. Middle West Press, 2022.

The war-writing scene knows well Randy Brown under his nom-de-plume Charlie Sherpa. Whatever name he goes by, Brown combines his own writing talent with endless support of other vet-authors. Now comes Twelve O’Clock Haiku, an ingenious amalgamation of critical reflections on the WWII Air Force classic-movie Twelve O’Clock High, haikus on the same, and a sampling of previous published verse. Avoiding cant, bromides, and tired wisdom about military leadership, Twelve O’Clock Haiku delights with insights that hit first as clever, and then as poignant and profound.

Eric Chandler, Kekekabic. Finishing Line Press, 2022.

Chandler, a retired Air Force pilot, wrote at length about war in his first book of poetry Hugging This Rock. War is barely mentioned in his latest collection Kekekabic, but lurks everywhere. Nominally a set of poetic meditations on a year spent running-and-hiking, the taut poetic forms Chandler employs—haibun and haiku—bespeak the “blessed rage for order” of a combat vet still simmering down from overseas war, even as cultural wars and politicized violence burns ever hotter on the home-front. The calm, observant wisdom on display in Kekekabic is the farthest thing imaginable from the overheated discourse of today’s public sphere, and all the better for it.

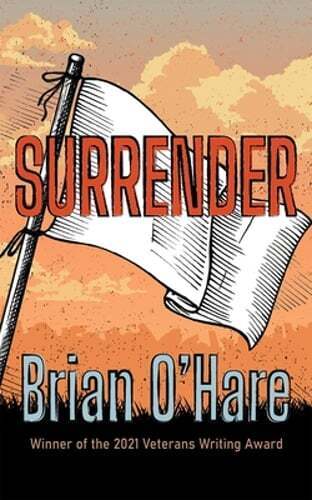

Brian O’Hare, Surrender. Syracuse UP, 2022.

O’Hare’s Iraq was Operation Desert Storm, not Iraqi Freedom, but the sensibility binding the linked stories featuring a disenchanted Marine lieutenant in Surrender will be very familiar to GWOT vets. Taking aim at toxic paternal authority, whether in the form of an overbearing combat-vet father, a tyrannical high-school football coach, or an incompetent and delusional Marine battalion commander, Surrender’s stories are remarkably varied, even, and accomplished. It took O’Hare thirty years to find his voice; his debt to GWOT war-writing is prominent in Surrender, which he well admits in this astute essay for Electric Lit titled “9 Books That Take Aim at the Myth of the American Hero.”

Jennifer Orth-Veillon, editor, Beyond Their Limits of Longing: Contemporary Writers and Veterans on the Lingering Stories of World War I. MilSpeak Books, 2022.

Featuring a who’s-who of contemporary war-writing authors, Beyond Their Limits of Longing asks its contributors to ruminate on an aspect of World War I that is personally meaningful and not generally well-known. Combining scholarship, personal essays, fiction, and poetry, there’s not a mundane piece among the 70+ chapters. Editor Jennifer Orth-Veillon astutely discerned that GWOT vet-writers’ connection to World War I—both the battlefields and the literature that resulted—might be profound, and Beyond Their Limits of Longing rewards that intuition in spades.

Ben Weakley, Heat + Pressure: Poems from War. Middle West Press, 2022.

I’ve yet to read Heat + Pressure, but if it’s published by Randy Brown’s Middle West Press and blurbed by Brian Turner, it’s got to be good. Its Amazon page relates that Weakley, an Army combat vet, found his inclination to write in post-service vet-writing workshops. That’s a story right there—one of the great through-lines of the vet-writing scene, now in its fifteenth year or so, is how writing workshops have encouraged writing initiative and created opportunity for talent to flourish.