Has anyone ever noticed that Time Now has never featured a post about video games and video game culture? Probably not, but the omission has long bothered me. “Video games” as a category may fit uneasily within this blog’s self-defined rubric of “art, film, and literature.” In my mind, though, the fantastically stylized, heavily aestheticized representational world of video games, especially first-person shooters (FPSs) and military role-playing games (RPGs), have much in common with the imaginary depictions of combat featured in traditional artistic-entertainment forms such as books, pictures, and movies about war. Both as an influence on real soldiers and as a commentary on modern warfaring, their importance is unquestionable. That I haven’t been able to articulate the linkage between video game popularity and a nation-at-war has seemed to me a huge shortcoming of Time Now. If there is anything that has made the blog stodgy and culturally out-of-touch, it is that.

This teeth-gnashing is linked to life, naturally, for I’ve never played so much as a second of a military-themed video game, even as my two sons have played many hours of Call of Duty under my own roof and many soldiers with whom I deployed played FPSs and RPGs whenever they could.

Given my near-neurotic diffidence to actually playing video games, I’ve done what I’ve always done in such cases: I turned to books for understanding of a phenomenon I was too hung up about to enjoy for myself. And yet, the pickings here so far have been slim. Until recently, the most substantial investigation of video games and modern war has been a great chapter in scholar Dora Appel’s War Culture and the Contest of Images that explores the popularity of America’s Army, a first-person shooter developed at West Point—get this—in the same building where I worked for ten years. I had never paid much attention to America’s Army before reading Appel and subsequently was driven to apoplectic wonder to learn that it was not just an effective recruiting tool (its intended use), but actually garnered respect from the hardcore gaming community. Fuck! What else has the Army done so well (and I have missed) in the last 15 years?

I say all the above to say this:

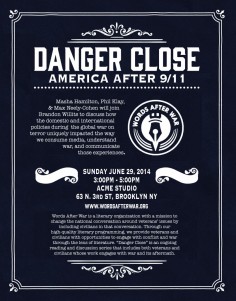

Last week, a New York City-based writer named Maxwell Neely-Cohen published on Boing Boing and the Armchair Empire an essay on video games and contemporary militarism called “War Without Tears: The Relationship Between Video Games and Violence Is Healthier Than We Think.” I knew the project was in the works, because I’ve met and chatted with Neely-Cohen at various war-lit events and surmised that if anyone could write a great essay on the connection between video game and martial culture, he could. Having worked as an intelligence analyst and the author of a cool coming-of-age novel called Echo of the Boom, Neely-Cohen combines writing chops with an ultra-alert mind thoroughly in tune with our generational moment. Himself a veteran gamer, he brings to the subject an insider’s savvy devoid of snoopy-pants suspicious judgmentalism many other writers, such as me, probably couldn’t avoid.

Neely-Cohen’s essay combines reportage, first-person experience, and the kind of speculative cultural commentary—pro-technology and progressively anti-authoritarian—you would expect from a website sponsored by anarcho-futurist-technophile author Cory Doctorow. Below are some snippets that set-up Neely-Cohen’s larger argument. I won’t explain or explore the full dimensions of his claims now—let’s just say they are bold and provocative, and I hope he’s right that video-game playing is “healthy”—but you can bet I’ll be thinking about them in the weeks to come.

Even with the success of movies like American Sniper and books like Phil Klay’s Redeployment, the most consumed artistic images of the past 14 years of American conflict lie in video games.

More people are pretending to fight wars than actually fighting them. What does this mean?

But in addition to these larger constructs, in some small cultural way, video games must have played at least some role in pushing the actual experience of warfighting further from the public mind.

At the same time, video games present a stark example of a civilian population increasingly disengaged from war and the military, a distraction from the violence which they portray.

Young people, particularly young men, can now fulfill that cultural and psychological obligation towards the experience of organized violence—without actually joining the military.