The concept of a “rhetorical triangle” is well-known to graduate students of composition, rhetoric, and communications. A way of imagining any particular act of communication, but especially that of public speakers and authors in the act of argument and persuasion, the rhetorical triangle attempts to depict the relationship between speakers and authors, their subjects, and their audiences. Graduate students ground their academic interest in the rhetorical triangle in Aristotelian definitions of ethos, pathos, and logos, each linked to a specific corner of the triangle, and put their understanding to practical use in undergraduate composition classes. There, the rhetorical triangle helps students understand the importance of author and speaker subject positions and the notion of intended audiences. Often, the rhetorical triangle is embellished in textbooks and slide presentations with the addition of circle that envelops the triangle, meant to represent “context”—why a particular subject is under discussion at all, what outside pressures bear on it, what underlying assumptions impact the effort being made at communication, etc. Figures A and B below depict the rhetorical triangle and the rhetorical triangle + contextual circle as they typically are represented.

All good, but I’ve long thought that the typical rhetorical triangle, as it exists as a visual metaphor, was a little too rigid, unsubtle, and unimaginative to portray the complexity of any “communicative situation,” to borrow another phrase from the rhetoric-and-composition world. My misgivings crystallized as I began thinking about how the rhetorical triangle might apply to war writing, by which I mostly mean fiction and poetry about war authored by veterans of war, though not without application to memoir, non-fiction, and veterans-in-the-classroom scenarios, as well as works written by journalists, historians, and civilian authors of imaginative literature who have studied war closely. Still, if we retain the basic equilateral triangle and round circle shapes of the standard rhetorical triangle + contextual circle, we might enhance it as follows in Figure C to portray what traditionally might be said to be the relationship of veteran-writers, war, and civilian readers who have not been to war:

As my thinking about this pictorial representation of war writing dynamics proliferated, or perhaps festered, I began to question whether the circle representing context adequately conveyed what is most salient about the attempt to render the experience of war to readers who had not seen combat. Rather than a benign circle hovering on the outskirts of the acts of writing and reading, I thought that a grid imposed over the top of the triangle might better depict how war writing as a genre is forcibly shaped by an array of recurring events, attitudes, themes, tropes, scenes, and expectations, as well as reliance on a short list of time-honored antecedents as literary models, that together harmfully solidified the relationships of writer, subject, and reader into hardened positions, perilously close to cliché, stereotype, “confirmation biased” patterns of cause-and-effect, and self-prophecizing conclusions. Figure D shows my effort to portray context as an imposed grid:

What might be a work of literature, or a movie, that could be given as an example of war writing that conforms to the Figure D model? There’s no perfect example—the diagram is a cartoon, after all—but let’s for the sake of argument posit works such as Stephen Crane’s The Red Badge of Courage and Erich Maria Remarque’s All Quiet on the Western Front as the ur-novels of modern warfare: stories that concern themselves not just with describing the “horrors of combat” and the possibility of transcending them, but the psychological effect of witnessing and enduring the horrors. Yes, I know Crane was not a veteran, but he ventriloquized one admirably, and like I said, the examples are not perfect. What’s important is that many many works of fiction, as well as memoirs and movies, have repeated, with various amounts of skill, motifs and manners-of-treatment originating or advanced in exemplary fashion by Crane and Remarque.

What might be a work of literature, or a movie, that could be given as an example of war writing that conforms to the Figure D model? There’s no perfect example—the diagram is a cartoon, after all—but let’s for the sake of argument posit works such as Stephen Crane’s The Red Badge of Courage and Erich Maria Remarque’s All Quiet on the Western Front as the ur-novels of modern warfare: stories that concern themselves not just with describing the “horrors of combat” and the possibility of transcending them, but the psychological effect of witnessing and enduring the horrors. Yes, I know Crane was not a veteran, but he ventriloquized one admirably, and like I said, the examples are not perfect. What’s important is that many many works of fiction, as well as memoirs and movies, have repeated, with various amounts of skill, motifs and manners-of-treatment originating or advanced in exemplary fashion by Crane and Remarque.

But as war writing evolved and permutated over the course of the 20th century, differences in style, perspective, and approaches also emerged. A very common refrain found in Vietnam War writing is the idea that “the truth of war cannot be conveyed,” sometimes expressed as “you had to be there to understand it,” notions that would seem to undermine the whole effort of writing about war. They didn’t, however, and in practice the sentiment seems to operate more as a marker of authenticity than a confession of ineptitude. The arch-expression of the idea is Tim O’Brien’s well-known “How to Tell a True War Story,” which compellingly dramatizes a veteran-author’s difficulty in conveying to civilians the essence of what fighting in Vietnam was all about. O’Brien’s famous last line, “It’s about sisters who never write back and people who never listen,” drives home the point that in the narrator’s mind at least one corner of the rhetorical triangle, that of the audience, is drastically estranged from both the veteran-author and whatever might be said to be the truth and reality of war.

A post-9/11 war reiteration of the fractured war-writing rhetorical triangle appears in Matt Gallagher’s novel Youngblood. In the Prologue, the narrator-veteran describes several instances of difficulty connecting with civilians who ask him what Iraq was like. He ends by stating,

What was it like? Hell if I know. But next time someone asks, I won’t answer straight and clean. I’ll answer crooked, and I’ll answer long. And when they get confused or angry, I’ll smile. Finally, I’ll think. Someone who understands.

Here, Gallagher’s narrator’s hoped-for “communicative situation” is marked by frustration and distortion, which, if only those miserable qualities could be attained, would stand as a great improvement on the incomprehension and indifference that have so far governed his attempt to describe war.

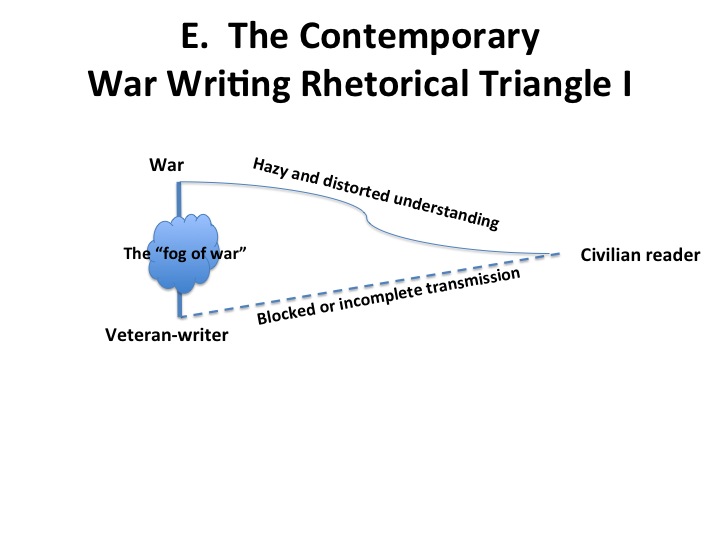

The contemporary emphasis on “failure to communicate” might be reflected in the following variation on the war-writing rhetorical triangle (Figure E):

Features of the contemporary model include:

- The veteran-author’s personal relationship to his or her subject of war is intense and intimate, as represented by a thickened, shortened line, but the connection is obfuscated by that very closeness, as well as the more general difficulty of apprehending the truth or reality of combat described as “the fog of war.”

- The civilian reader’s relationship to the veteran-writer, and vice-versa, is distant and beset by communication difficulties, as portrayed by the long, broken line.

- The civilian reader’s understanding of war is also remote, indistinct, and untrustworthy, as depicted by the thin, wavering line.

In Figure F below, I have added in a contextual circle that names what I think are the most important contemporary social, political, cultural, and technological influences on war, the men and women who go to war and then write about it, and the nation-at-large. I’ve also noted some changes in the composition of the corners of the triangle to reflect modern trends.

I won’t take time here to explain these factors or how they put pressure on the legs and corners of my war writing rhetorical triangle. Many are obvious or self-explanatory, and none are beyond the ken of readers who have made it this far and who now choose to roll them around in their minds to consider their relevance. I might well have portrayed them as a grid, as in Figure D above, but for the sake of clarity, mostly, I haven’t. Taken together, the diagram suggests a contemporary war writing field characterized by multiple variables, full of complexity, ambiguity, perspectival variations, and tenuous, arguable intersections joining war, writing about war, and readers.

Might the broken-and-distorted contemporary war writing rhetorical triangle be as much a trope, or even a cliché, as anything that’s come before? Some very good veteran-authors have taken up the question. Benjamin Busch, in “To the Veteran,” his introduction to the veteran writing anthology Standing Down: From Warrior to Civilian, states, “We often feel there is a certain authenticity lost somewhere, that language cannot completely express our experience to those who do not share it,” but ultimately he concludes that the stories in Standing Down “prove that transference of experience is possible with language.” Similarly, Phil Klay in a New York Times essay titled “After War, A Failure of Imagination,” writes, “Believing war is beyond words is an abrogation of responsibility — it lets civilians off the hook from trying to understand, and veterans off the hook from needing to explain.” Busch and Klay are formidable writers, but I’m not sure everyone, including many veterans, agrees that veterans can express the reality of war in a way that is perceived as meaningful and reasonably fulsome by civilians. The fact that Busch and Klay have to assert their case proves the sentiment they hope to rectify is both real and a problem. Whether their perception is an enduring and truly true structural feature of war writing or merely a passing truism-of-the-day remains to be seen.

Many thanks to the organizers and participants of the 2016 Veterans in Society seminar at Virginia Tech, where I first presented on the “War Writing Rhetorical Triangle.”