Three weeks have scarcely passed, at any time between then and now, that I have not unfolded within myself. -Herman Melville to Nathaniel Hawthorne, while writing Moby-Dick.

Since I began Time Now eight years ago, easily a hundred books, films, plays, musical compositions, and other artworks about America’s post-9/11 wars written-and-composed by veterans and interested civilians have appeared, and much has been published online, too. Here I catalog and comment on six author-artists whose individual output has been robust, often across a variety of genres and artistic mediums, and I mention several more who have been almost but not quite as active. I’ve limited myself to US military veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan and used books published by major publishing houses as the primary (but not only) criteria for inclusion.

Elliot Ackerman (USMC) arrived late to the war-writing party, but has quickly made up lost time by publishing three novels since 2015: Green on Blue (2015), Dark at the Crossing (2017), and Waiting for Eden (2018). A memoir titled Places and Names: On War, Revolution, and Returning (2019) will appear later this year. Ackerman also contributed a story titled “Two Grenades” to The Road Ahead (2017) anthology of veteran-authored fiction. Links to Ackerman’s journalism and other occasional writing can be found at http://elliotackerman.com.

The characteristic subject of Ackerman’s novels is a fringe-actor on the margins of America’s 21st-century wars: a Pashtun militiaman on the Afghanistan-Pakistan border, an Iraqi who formerly interpreted for American forces now trying to join the Syrian civil war, the wife of a severely wounded Marine who keeps a lonely vigil over her disabled husband, both largely abandoned or neglected by the greater America. In his published work so far, then, Ackerman has avoided the solipsistic trap of writing about his own (substantial) war experience as if it were the only thing that matters. In his upcoming memoir Places and Names, however, Ackerman begins to stitch together autobiographical elements and his interest in the people who fight the wars that, to paraphrase a John Milton quote on the cover of Places and Names,“hath determined them.”

Benjamin Busch (USMC) was arguably the first contemporary veteran to turn war experience into aesthetic expression, as the photos-and-commentary that would eventually comprise The Art in War first began appearing in 2003. Befitting his college background as a fine arts major, Busch also displays, again arguably, the most artistic diversity: he has acted in The Wire (2004) and Generation Kill (2008), directed films such as Bright (2011), authored a memoir titled Dust to Dust (2012), written a striking set of nature poems for the journal Epiphany (2016), and contributed both a short story (“Into the Land of Dogs”) and hand-drawn illustrations to The Road Ahead (2017) anthology. Busch has also written incisive reviews of the movie Lone Survivor and contemporary war fiction, long-form journalism for Harper’s about a return visit to Iraq, a poignant contribution to the vet-writing anthology Incoming titled “Home Invasion,” and an eloquent introduction to another anthology titled Standing Down. Oh, and let’s not forget a pre-Marine life as the singer in a hair-metal band.

A superb stylist, Busch is the master of the apt image and the well-turned line, sentence, passage, or short poem, with his memoir Dust to Dust being the book-length exception that proves the rule. Busch’s thematic impulse is to find order and meaning in randomness, disorder, and chaos. The urge is on full display in The Art in War and manifests itself even more intensely in Dust to Dust and “Home Invasion”; in these works, loss, ruination, and mortality emerge as the most salient organizing imperatives to be found, save for the author’s own imagination. War, irrational and death-soaked, was Busch’s subject starting out, but more recent poems such as “Madness in the Wild” suggest that Mother Nature is now the most fertile source of material for Busch’s “blessed rage for order,” to borrow from Wallace Stevens.

Brian Castner’s (USAF) first published book was the war memoir The Long Walk (2012), followed by a second book titled All the Ways We Kill and Die (2016) that combines more war memoir with journalistic investigation. A third work, not (directly) related to war, Disappointment River: Finding and Losing the Northwest Passage (2018), joins travel-memoir and historical research. An opera has been made of The Long Walk, and Castner, with Adrian Boneberger, edited The Road Ahead (2017), an anthology of veteran-authored fiction to which he also contributed a story called “The Wild Hunt.” Journalism, essays, and reviews by Castner can be found at https://briancastner.com/.

While Castner’s memoir The Long Walk contains elements of artistic heightening that appealed to the opera composers who adapted it, the next two books are the ones that best illustrate Castner’s forte: extensive historical and journalistic research that supplements the lived experiences of his own life—first serving as an EOD-technician in the case of All the Ways We Kill and Die and then making a thousand-mile canoe journey in the case of Disappointment River. The influence of war on Disappointment River may bubble below the surface (pun intended), but the surface impression is that Castner more so than most other war-writers can find subjects beyond war-and-mil ones that still command the full measure of his interest and talent.

Matt Gallagher (US Army), with Colby Buzzell, pioneered the use of the Internet as a means of literary arrival when his war-blog appeared in book form as Kaboom (2010). Gallagher next edited the seminal vet-fiction anthology Fire and Forget (2013) with Roy Scranton and contributed to it a story titled “Bugs Don’t Bleed.” Then arrived the novel Youngblood (2016) and two short stories, “Babylon” (2016), published in Playboy, and “Know Your Enemy” (2016), published in Wired. Gallagher also has served at the forefront of the veterans writing scene, as a prime mover in first the NYU Veterans Writing Workshop that gave birth to Fire and Forget and then the New York-based collective Words After War. A number of Gallagher’s occasional pieces can be found at http://www.mattgallagherauthor.com/disc.htm and a second novel will arrive soon.

A consistent tone connecting Gallagher’s own voice and that of his fictional characters is sardonic detachment from the full negative import of the events they experience; in other words, Gallagher tests the limits of irony and perspective as means of dealing with the confusion of war and the resultant damage to self and society. Bemusement would seem to be an underpowered coping strategy in these troubled times, but Gallagher’s amiable prose surfaces welcome readers to consider his point-of-view long enough that the darker cynicism and deeper commitment lurking within eventually reveal themselves and grab hold.

Roy Scranton (US Army) published short stories and poems in small journals before co-editing Fire and Forget (2013) with Matt Gallagher and contributing a story to it titled “Red Steel India.” Next came the philosophical treatise Learning to Die in the Anthropocene (2015), the novel War Porn (2016), an anthology titled What Future: The Year’s Best Ideas to Reclaim, Reanimate, and Reinvent Our Future (2017) for which he served as editor, and a collected edition of essays and journalism titled We’re Doomed, Now What? (2018). Later this year will arrive a literary history titled Total Mobilization: World War II and American Literature (2019) and a novel called I ♥ Oklahoma (2019). More journalism, essays, short stories, and reviews can be found at http://royscranton.com.

There’s busy, and then there’s Roy Scranton busy, but the extraordinary rate of production and the prickly integrity of the viewpoint are endearing counterpoints to the starkness of the message: Scranton is ruthless in his indictment of the Iraq War in which he served, and he’s not letting anyone from enlisted “Joe’s” to generals to civilian war architects to a passive citizenry off the hook for their complicity in the debacle. Though he’s never quite said so bluntly, the implication is that vet-authors, whose ink might well be the blood of war dead, should seriously consider their own culpability, too. Scranton unsparingly connects America’s spastic post-9/11 response to Islamic fundamentalist violence with a host of other social, political, and environmental ills brought about by what academics like to call “the cultural logic of late capitalism.”

Brian Turner (US Army) arrived on the literary-artistic scene seemingly fully-formed, as his first poetry volume Here, Bullet (2005) won enormous acclaim from critics, readers, and poetry insiders alike. Next came a second volume of poems titled Phantom Noise (2010), an anthology of writing about poetry he co-edited titled The Strangest of Theaters (2013), a contribution to the Fire and Forget (2013) anthology titled “The Wave That Takes Us Under,” the memoir My Life as a Foreign Country (2014), and another co-edited anthology titled The Kiss (2018). Turner has also had a number of his poems set to music, perhaps most significant of which is a collaboration with composer Rob Deemer on Turner’s poem “Eulogy.” Turner makes music himself, first as a member of The Dead Quimbys and more recently as the leader of The Interplanetary Acoustic Team. Occasional writing can be found at http://www.brianturner.org.

A wise, inspirational senior-statesman within the war-writing community, Turner combines encouragement of fledgling writers with an uncanny ability to stay one or more steps ahead of the pack in terms of vision, craft, and surprising shifts of direction. The artistic tension manifest in Turner’s work is the product of two imperatives: the martial heritage bequeathed to him by family, culture, and history, and his natural impulse to be empathetic, curious, kind, and helpful. His latest works each in their way represent solutions or, better, absolutions, for the tension; the music of The Interplanetary Acoustic Team invokes a collective cosmic spirit and consciousness, while The Kiss sanctifies physical intimacy as a hallowed form of human connection.

****

Several veteran writers are one or two published works short of joining the author-artists I name above. For these writers, their NEXT work will be most interesting for how it confirms previous inclinations and preoccupations, modifies them, or points in new directions:

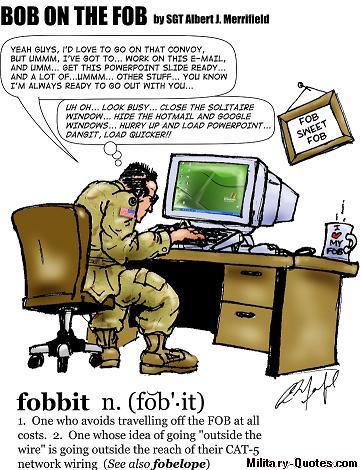

David Abrams (US Army) has published two novels, Fobbit (2012) and Brave Deeds (2017), and he contributed “Roll Call” to the Fire and Forget (2013) anthology. Shorter pieces can be found at http://www.davidabramsbooks.com. Abrams’ gift for creating characters, sketching scenes, and writing pleasing and often very funny sentences is substantial. So far, his interest seems to be the cultural divide separating rear-echelon soldiers from their hardened warrior-brethren in the combat arms; given his comic and warm-hearted sensibility, his modus inclines to exposing foibles associated with military masculinity rather than harshly judging and accusing their owners.

Colby Buzzell (US Army) pioneered the blog-to-book trend with My War: Killing Time in Iraq (2005) and he later published two books of essays and journalism: Lost in America: A Dead End Journey (2011) and Thank You for Being Expendable, and Other Experiences (2015). The only work of fiction of which I’m aware of is his story “Play the Game” in the Fire and Forget anthology (2013), but Buzzell’s hostility toward authority and power, his affinity for oddballs and misfits, and the verve of his sentences create the impression of a distinctly “punk” literary sensibility–one that has proven very popular and influential. Buzzell’s webpage contains links to his writing that can be found online: http://www.colbybuzzell.com/stories.

Phil Klay (USMC) contributed the short story “Redeployment” to Fire and Forget (2013), which later became the title story of his National Book Award-winning short-story collection Redeployment (2014). A large number of essays and long-form journalism pieces are at http://www.philklay.com. Klay’s characteristic concern is the moral culpability of soldiers who joined the military and did their bit in Iraq or Afghanistan without too much post-war mental anguish or blood on their hands—to what extent should they (be made to) feel worse (in another word, guiltier) than they do about their decisions and actions? For me, that’s the subject of two representative stories in Redeployment, “Ten Klicks South” and “Prayer in the Furnace,” as well as that of the long, trenchant essay Klay published for the Brookings Institute titled “The Citizen-Soldier: Moral Risk and the Modern Military.” Finally, although I’m not sure when Klay’s next book will appear or what it will be about, while we wait for it, I recommend listening to the intellectually-knotty podcast Manifesto! Klay hosts with fellow vet-writer and Fire and Forget contributor Jacob Siegel.

Kevin Powers (US Army)’s first novel was The Yellow Birds (2012). Next came the poetry volume Letter Composed During a Lull in the Fighting, followed by a second novel A Shout in the Ruins (2018). Journalism, essays, and reviews can be found at http://kevincpowers.com. It’s easy to forget the hullabaloo that greeted The Yellow Birds upon arrival. Following upon Brian Turner’s Here, Bullet and Army spouse Siobhan Fallon’s short-story collection You Know When the Men Are Gone (2011), The Yellow Birds reinforced the notion that 21st-century American writing about the war was going to cook at a very high literary level. But the backlash against The Yellow Birds arrived just as quickly, as for many it promoted and even celebrated the idea that modern American soldiers were easily-traumatized snowflakes too tender to win wars. In the wake of The Yellow Birds, a counter-formation of memoirs and short-stories appeared, stories of war by ex-combat-arms bubbas seemingly delighted to assert that they were hard men capable of doing hard things. I’m not inclined to be harsh in my assessment of The Yellow Birds, but Powers seems to have distanced himself from his poetry volume, and I haven’t yet read A Shout in the Ruins, so categorical statements about the arc of his career will have to wait.

Kayla Williams (US Army) has written two memoirs, Love My Rifle More Than You: Young and Female in the US Army (2005) and Plenty of Time When We Get Home: Love and Recovery in the Aftermath of War (2014). Williams has also contributed a short-story, “There’s Always One,” to the veteran-writer short-story anthology The Road Ahead (2017). Given her job as a Washington DC think-tank analyst and the impression she renders that she’s bound for big things in the public sector, it’s not hard to imagine a third memoir might be needed someday to document further chapters in Williams’ life. Detailing the long story of any vet’s life (especially a woman vet’s) after war will be immensely interesting and valuable, but I hope in the future Williams finds time to write more fiction, too.

Quite a few other writers merit consideration for inclusion on this list. Among them are Adrian Bonenberger (US Army, Afghan Post, memoir; The Road Ahead, fiction anthology editor (with Brian Castner); “American Fapper,” story in The Road Ahead); Maurice Decaul (USMC, Dijla Was Furat: Between the Tigris and the Euphrates, play; multiple poems published in small journals and online; a musical collaboration with contemporary jazz great Vijay Iyer); Colin Halloran (US Army, Shortly Thereafter and Icarian Flux, poetry); Hugh Martin (Stick Soldiers and In Country, poetry); Brian Van Reet (US Army, “Big Two-Hearted Hunting Creek,” short-story contribution to Fire and Forget and much short-fiction published in literary journals; Spoils, novel). Three women Iraq-Afghanistan veterans, Teresa Fazio (USMC), Kristen Rouse (US Army), and Supriya Venkatesan (US Army), write with distinctive voice and great eye for the telling subject and detail, and each has published widely, though more in the vein of journalism, memoir, and essay than fiction or poetry (the exceptions being Fazio’s and Rouse’s stories “Little” and “Pawns,” respectively, both included in The Road Ahead anthology), and none has yet found book-length publication.

My judgments about each author’s body-of-work are far from beyond dispute, and I welcome discussion, as well as any factual corrections to the record. An extended contemplation about the collective import of these writers is in order, but I’ll end with just two brief points: 1) The accomplishment of these vet writers is substantial and the potential for further achievement is strong; barring misfortune, everyone I’ve mentioned still has decades of productive creative life to come. 2) Women veteran-authors and male or female African-American, Hispanic, and Asian-American vet-writers are noticeably missing. If I’ve overlooked a worthy candidate to add to the list, let me know, and if conversation about publishing trends and marketplace dynamics interests you, let’s talk about that, too. Though my focus here is the unfolding of a writer-artist’s characteristic concerns over multiple works, the story is also one of professional ambition, literary politics, and publishing biz calculation. What I’m describing as the birthing of an estimable generation of veteran-writers, another may see as the solidifying of a literary establishment limited by its own blinders and mostly interested in preserving its own prerogatives. That’s not how I feel about it, but I hope that should I compile this list again in another eight years, the demographic make-up will reflect the military in which I served and the overall achievement so much the better.