In 1999 US Army forces deployed to the Serbian province of Kosovo as part of a peacekeeping mission to halt the killing and forced relocation of the region’s majority Muslim Albanian population by Christian Serbs. In the two years prior to the American-led intervention, Kosovo Serbs, backed by the Serbian army, used violence to halt a demographic makeover they feared would sever the region’s political and cultural allegiance with greater Serbia. Some 1,500 Albanians were killed and 400,000 driven from their homes by Serbian military, police, para-military forces, and local zealots.

The American intervention, part of a NATO-led task force known as “KFOR,” was largely successful, in that Serbian-Albanian violence quickly diminished. The province began to develop a political identity as an Albanian-dominated independent state that culminated in a declaration of sovereignty in 2008. The KFOR mission, on the heels of and modeled after the bigger US and NATO peacekeeping effort in Bosnia-Herzegovina earlier in the decade, continues today, but consists of less than 700 US soldiers in Kosovo at any time. By another measure of bottom-line cost—American casualties—the mission has also been successful. In the years since American forces first put “boots on the ground,” fewer than twenty Americans have died in Kosovo, most as a result of illness or accident. For whatever reasons, the “Global War on Terror” following 9/11 has been able to quell or ignore Christian-Muslim tension in the Balkans. While war raged and then dragged-on in Iraq and Afghanistan, KFOR has also continued, largely peaceful and out-of-the-spotlight. As early as 2001, when the infantry battalion I was part of rotated into the US sector and took up residence at Camp Monteith near the northeastern city of Gnjilane, the KFOR mission had a decided side-show quality in the Army at large and the world’s mind as well. A sister battalion from our brigade was already fighting in Afghanistan, and many of us were jealous of them beyond words because they were where the action was, and we weren’t.

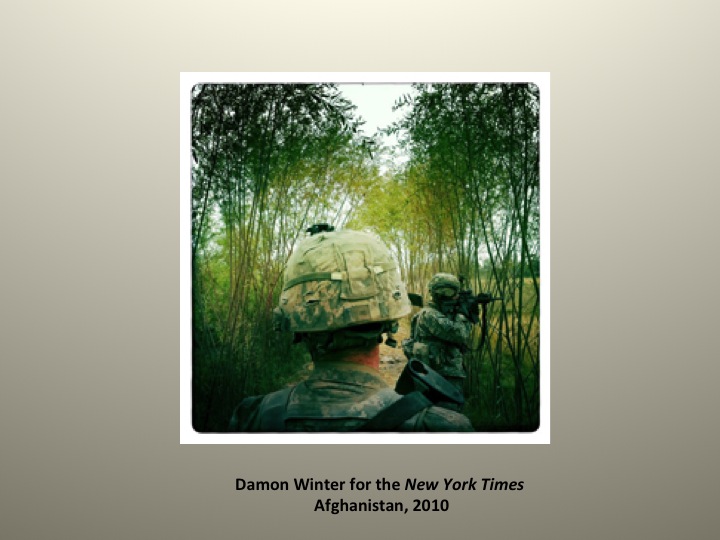

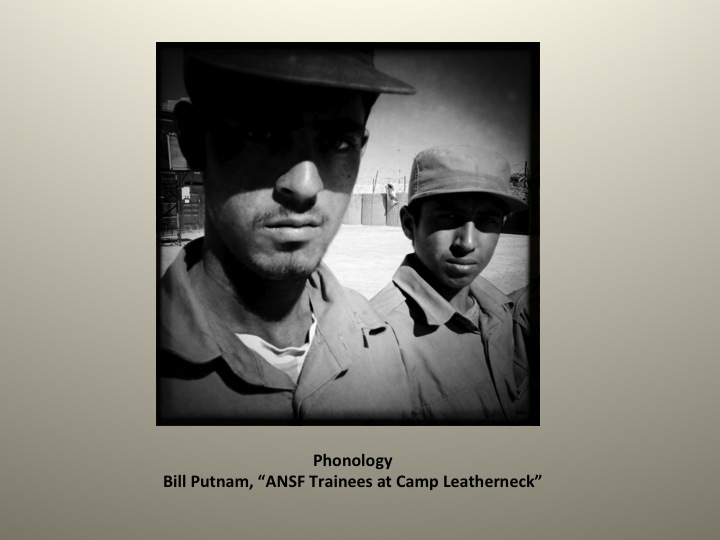

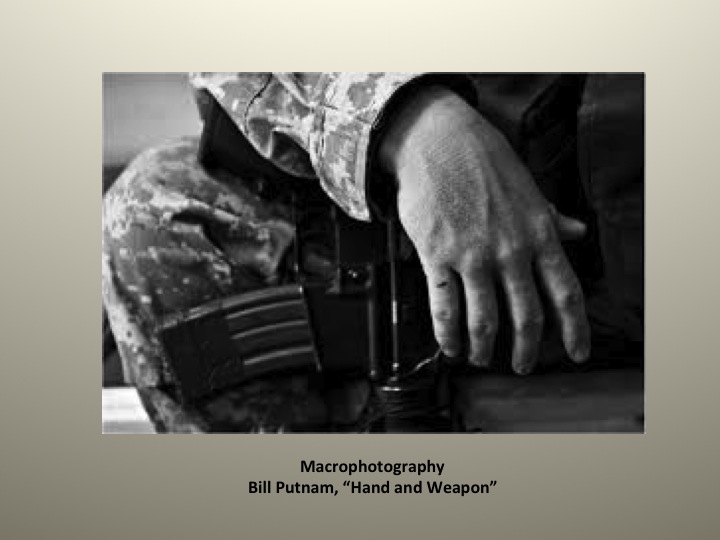

Photographer Bill Putnam was a soldier in the Public Affairs unit of the infantry task force of which I was the executive officer, or second-in-command. Putnam would return to Kosovo in 2002 and go on to take striking photographs in Iraq while still in the Army and later as an embedded photojournalist in both Iraq and Afghanistan.

Only recently I returned to look closely at Putnam’s archive of Kosovo pictures. My sense was that Army operations in Kosovo foreshadowed and rehearsed similar approaches the US military would employ in Iraq and Afghanistan. As late as 2001, though, the material appearance of American soldiers was different from what it would soon come to be. But if one looks closely one can see not traces of a vanished past, but a soon-to-be-present future in the process of its emergence.

Putnam’s photographs for the most part have a long-ago and far-away feel that sets them apart from his war photography of Iraq and Afghanistan. Part of it is the landscapes are different—European farms-and-forests, not southwest Asian cities and desert. So, too are the white faces of the Kosovars and their Western dress.

It is also the uniforms—US soldiers are dressed in their dark-green “Battle Dress Uniforms” just prior to giving them up for the desert camouflage of “chocolate chips” and “Army Combat Uniforms.” Not only are the uniforms of an older vintage, but so too is the equipment—load bearing web-gear, canteens, and M16 rifles, not armored vests, Camelbacks, and M4s. The visages of officers and enlisted men reflect purposefulness and enthusiasm, not anxiety, doubt, or confusion.

American forces patrolled in unarmored vehicles, usually in pairs but often individually. IEDs were unheard of and ambushes only a remote concern. The biggest danger was sliding off the narrow roads, especially in winter, when they were very icy. US KFOR forces often interacted with other members of the coalition, such as the two Russian soldiers standing at a checkpoint in the picture second below.

Cramped, impoverished villages built of shoddily-constructed concrete blocks vaguely resembled picture-postcards of European life. They conveyed a sense of provincialism and backwardness that would easily acquiesce to superior American ways of dealing with problems.

Cities were more bustling. Residents seemed too preoccupied by everyday life to kill in the name of politics and religion. But by the time we arrived, the Albanian makeover was nearly complete. Serbs huddled forlornly in their own neighborhoods and enclaves, and we protected their churches, not Muslim mosques, from destruction.

Overall, though, violence was rare, and could be handled with “crowd control” techniques, not combat.

Serbians and Albanians eager to fight were seen as hooligans with local agendas and grievances, not as operatives in a larger nationalist movement or global jihadist conspiracy. Detaining a troublemaker required extensive chain-of-command coordination, but the feel of such operations was that of locking up a small-town punk in the county jail for a few days until his anger subsided.

Most missions were “key leader engagements” with local officials, always negotiated with the help of interpreters, many of them women, wearing US Army camouflage.

American forces lived on Camp Monteith, an old Serbian Army base, and Camp Bondsteel, a proto-FOB magically construed out of nothing in an abandoned field by well-paid contractors. Many soldiers never left Monteith and Bondsteel, encampments complete with pizza parlors and Morale, Welfare, and Recreation centers. Mortar and rocket attacks that threatened the lives of soldiers on the camps just didn’t happen.

Kosovo allowed the US military to rehearse deployment, peacekeeping, and counterinsurgency tasks that would later characterize Operations Iraqi and Enduring Freedom. FOB life, vehicle patrols, religious conflict, security operations, interpreters, and key leader engagements seemed manageable and relatively benign. Very often though, KFOR approaches, such as traveling in one or two vehicle convoys, would prove inadequate for dealing with far-deadlier threats to come. Missions that were routine in KFOR metastasized in Iraq and Afghanistan and become much more fraught. What came peacefully and relatively easily in Kosovo might have inspired a false confidence in US capability that quickly unraveled in Iraq and Afghanistan. Hints of all this, I believe, can be found in Putnam’s photographs, if one knows where and how to look.

On the right of the picture below is Captain David Taylor, a company commander in our infantry task force. The picture is taken on Hill 874 outside Gnjilane, Kosovo in 2002. In 2006, Major Taylor was killed by an IED in Baghdad, Iraq.

More Bill Putnam photography can be found here.