The photojournalist creed is that news photographs are neither staged nor edited. Credibility depends on the collective belief of editors, readers, and peers that a photojournalist’s work represents objective reality. Of course there is artistry and craft involved in technical choices about cameras and film and in subjective decisions about which frame of many to transmit and publish. But the basic premise is that photographs, especially those taken of conflict, constitute reliable documentary evidence.

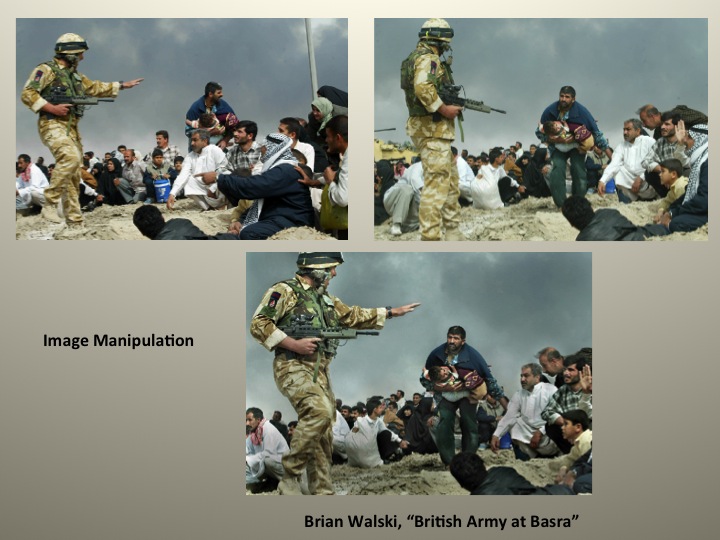

Photojournalist Brian Walski, for example, was scandalized early in the Iraq War when he merged two pictures together to create a more striking image that was subsequently published in the Los Angeles Times. Walski was fired and the Times forced to issue an apology for violating press photography ethical prohibitions on altering original photographs.

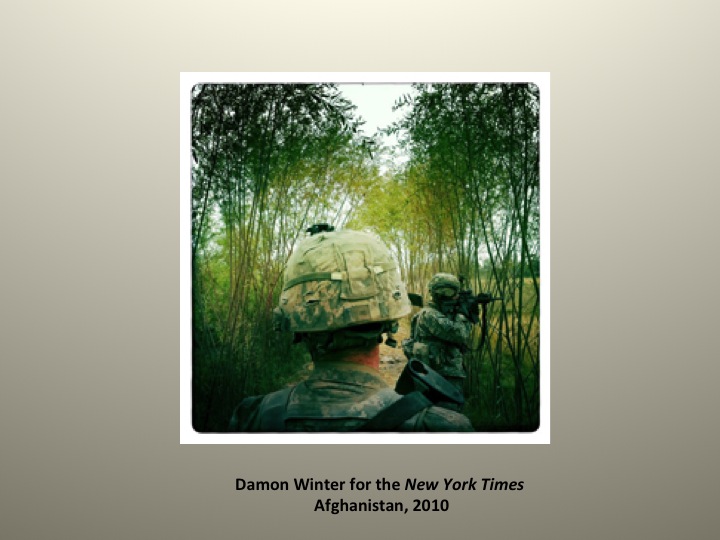

Later, New York Times photographer Damon Winter earned prizes for photographs taken in Afghanistan with an Iphone. But controversy arose concerning Winter’s use of the Hipstamatic editing app. To photojournalist purists, doing so represented an egregious after-the-fact manipulation of images meant to register as “authentic” and “credible.”

But Winter was not the only one who experimented with up-to-the-minute apps and techniques. Ann Davlin, in an article for the photography website Photodoto called “The Latest Photographic Trends to Defeat Your Competitors,” surveyed Instagram to determine what were the most popular editing tricks of the first decade of the new millennium–a period that roughly coincides with our contemporary wars. Intrigued by the article, I searched the Internet and my own stock of photographs for war images that also illustrate the techniques Davlin describes.

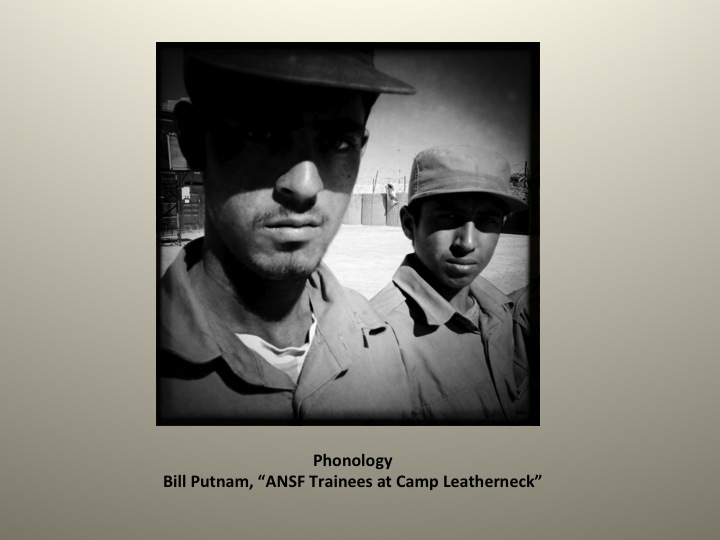

The most popular trend Davlin notes is one I’ve already mentioned: “phoneography,” or the use of phone cameras. I’ve featured Bill Putnam’s work many times on this blog because I think the world of it. Putnam is a hardcore camera geek who Tweets things like “The @16x9inc adapter is Heavy. Solid. Huge, bigger than I expected. But workable. Same compression of a 60 but view of a 27. #dlsr #video.“ But on his last deployment to Afghanistan, he took many pictures with an Iphone and used Hipstamatic to enhance them. The Iphone, he reports, was just ever-handy, and potential subjects rarely blanched at requests for pictures.

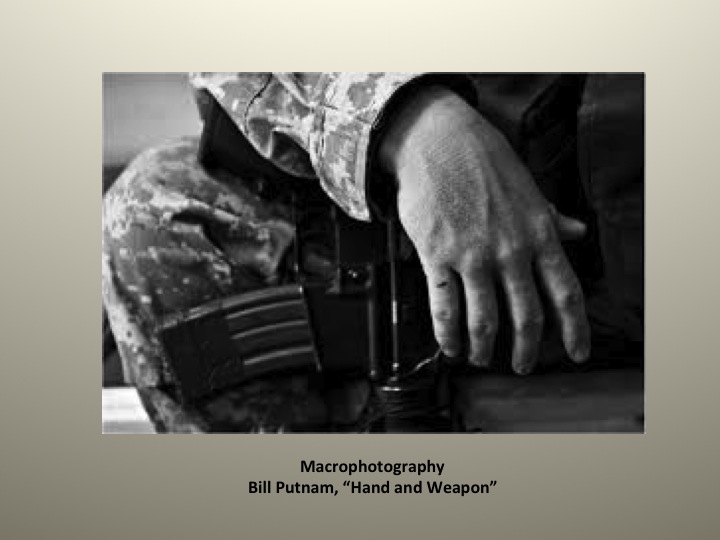

Second on Davlin’s list is “macrophotography,” or extreme close-ups. Again I’ll use a Bill Putnam example:

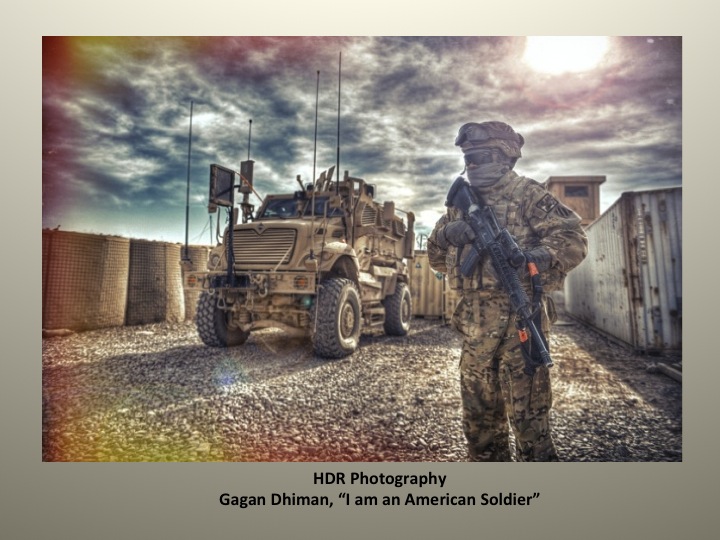

“HDR photography” refers to “high dynamic range” manipulation and editing of images to create special lighting effects. Sounds technical, but you’ll recognize the effect as soon as you see it below:

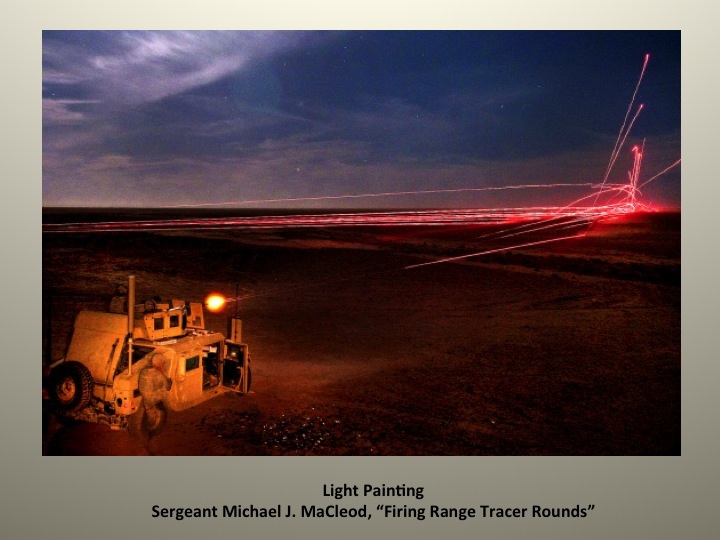

“Light painting” refers to emphasizing or highlighting streaks of light:

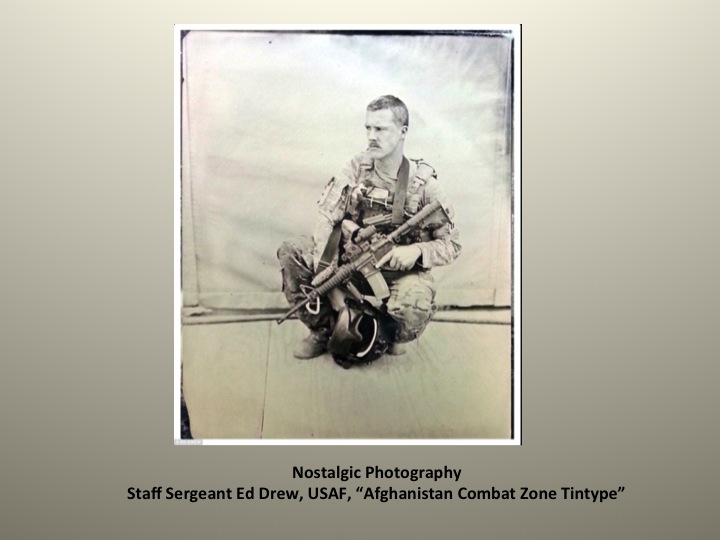

Davlin’s next category is “nostalgic photography,” or the creation of vintage effects through the use of apps such as Hipstamatic. USAF airman Ed Drew took nostalgic photography a step further by actually employing 19th-century tintype techniques to capture pictures of his fellow airmen in Afghanistan:

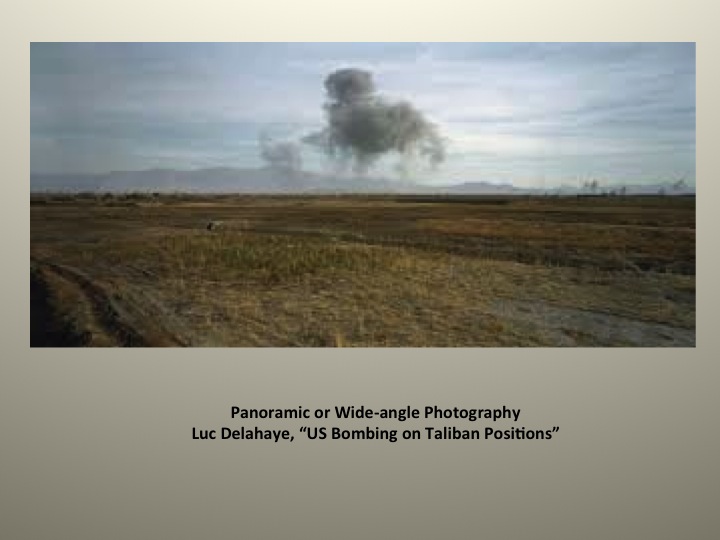

“Panoramic” or “wide-angle photography” is the last of the popular special effects listed by Davlin. A great example is below:

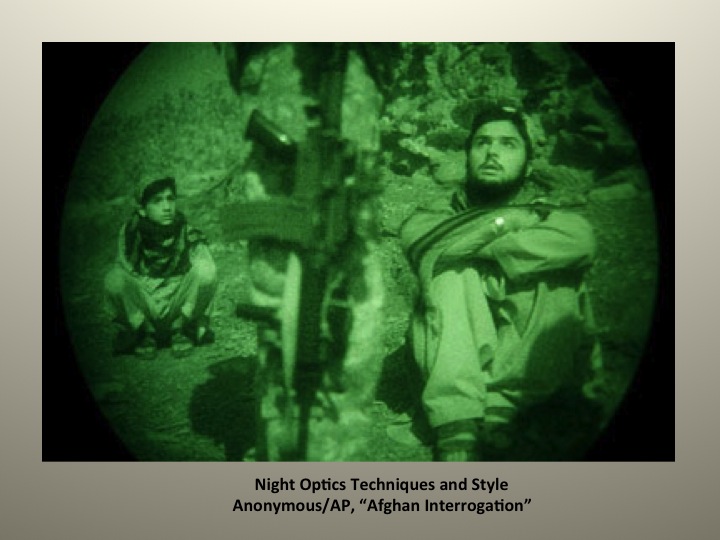

In addition to the categories proposed by Davlin, a few other motifs or trends exemplify contemporary combat photography. The first is night optic technique and style:

The second is not so much a style or technique but a contemporary means of distributing and consuming images: photography (and video) that reflects the influence of reality TV, video share services such as YouTube, TV news video, and close circuit surveillance aesthetics. The video below, taken by a security camera at a small outpost in Afghanistan, is not for the faint-hearted. Live footage taken about five miles away from where I was at the time, it shows a car bomb explosion that killed 13 Afghan children.

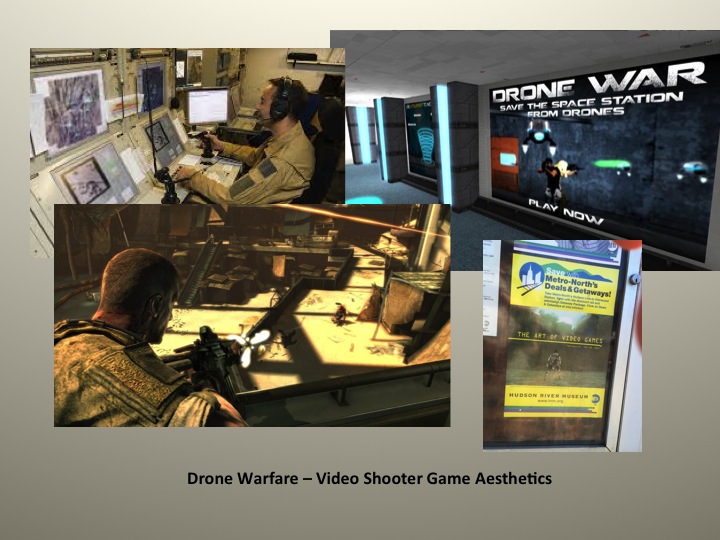

My final category is photography that reflects the aesthetics of drone warfare or first-person shooter games. My examples are not actual photographs from the warzones, but I little doubt that envisioning the war from the aspect of a UAV reigning carnage from the sky or a soldier aiming down the barrel of a weapon permeates our optical sense of how the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan have unfolded:

War photojournalism and artistic photography bring to the fore questions about treating violence and suffering as aesthetic subjects. How are we supposed to respond when we view graphic images that seem to glorify or prettify war? On what terms can a graphic image be considered beautiful? The ethical and aesthetic questions become even more complicated when photographers self-consciously manipulate images using the latest technology to generate effect. I’ll have more to say on these questions in future posts.

Terrific piece, LTC Molin. Great guide – and really interesting, comprehensive take on contemporary war photography. Well done, and thank you!

Thanks much, Adrian. I’d say more of a conversation starter than “comprehensive,” but I’ll take what words of praise I can get! More to come, too, in coming posts.

I have the book “Photographers on War” per your suggestion at work. Tomorrow when I get in I’ll examine the pictures for some of the techniques you talk about.

As for light painting, recently I saw a picture of a German machine gun firing tracer bullets at an allied position during WW2. The German tracers arcing down on the position. Imagine the panic of being on the receiving end of the onslaught as the shooters walk the stream in. And too imagine the shooters hoping they could silence what they were shooting at before their position,

given away by the tracers, is blown to bits by a tank or bazooka.

These photo techniques are powerful. Sometimes I can feel the adrenaline dumping into my bloodstream as a look at them.

Thanks, John. Many writers, fact and fiction, have described the beauty of outbound tracers, but I can’t recall any descriptions of inbound tracers. One thing to remember is that for every tracer round going out, four more non-tracer rounds are also speeding to the target.

The book John refers to is Michael Kamber’s Photojournalists on War: The Untold Stories from Iraq. It’s an important compendium of war photography accompanied by accounts by the photojournalists who took them. Kamber’s overarching point is that our visual understanding of the war was mediated, or compromised, at many levels. The military, the media, and sometimes the photographers themselves censored the publication of images that reflected poorly on the American mission or were deemed just too graphic for public taste.