When Bowe Bergdahl disappeared from his small combat outpost in Paktika province in 2009, I was also in eastern Afghanistan. In the ensuing days I obtained a pretty solid first-hand understanding of the tumult the event caused. After a month the story faded from public view, but it lingered long in my mind as one of the most curious, unexplained, unfinished episodes of the war. What would have made Bergdahl do that? Why did so few other soldiers do the same thing? The furor after his release by the Taliban a couple of weeks ago confirmed my intuition that his story was captivating and important.

Earlier this spring, I met a vet author who told me that he had written a draft of a novel based on the Bergdahl saga. For him, Bergdahl’s disappearance represented a contemporary version of Tim O’Brien’s 1978 Vietnam novel Going After Cacciato. In O’Brien’s novel, the title character slips away from his platoon while on patrol and tries to walk to Paris. It’s possible that Bergdahl, a reader and dreamy young man by all accounts, has read Going After Cacciato. But what is the larger import that accounts for the public fascination with his case? To me, Bergdahl enacted in real life a narrative that figures often in contemporary war lit, drama, and film—the dream of unofficial-but-honest unmediated contact between US service members and local national citizens. The movie The Hurt Locker provides the most available example—a soldier on his own slips the FOB perimeter to help a poor Iraqi family. I’ve seen two plays that also feature such scenarios, and I know there are others. Most portray such ad hoc interactions as kindly–soldiers now more human once free of military tyranny–but others show Americans acting evilly–enflamed by military dehumanization and now free of its discipline, they run wild.

Earlier this spring, I met a vet author who told me that he had written a draft of a novel based on the Bergdahl saga. For him, Bergdahl’s disappearance represented a contemporary version of Tim O’Brien’s 1978 Vietnam novel Going After Cacciato. In O’Brien’s novel, the title character slips away from his platoon while on patrol and tries to walk to Paris. It’s possible that Bergdahl, a reader and dreamy young man by all accounts, has read Going After Cacciato. But what is the larger import that accounts for the public fascination with his case? To me, Bergdahl enacted in real life a narrative that figures often in contemporary war lit, drama, and film—the dream of unofficial-but-honest unmediated contact between US service members and local national citizens. The movie The Hurt Locker provides the most available example—a soldier on his own slips the FOB perimeter to help a poor Iraqi family. I’ve seen two plays that also feature such scenarios, and I know there are others. Most portray such ad hoc interactions as kindly–soldiers now more human once free of military tyranny–but others show Americans acting evilly–enflamed by military dehumanization and now free of its discipline, they run wild.

I can surmise that such portraits represent efforts to illustrate the human side of war, but I doubt they ring true with many vets. Most I think would find them unrealistic if not downright dopey. In my experience soldiers didn’t care enough about Afghans or Iraqis to even think about risking their lives by leaving the safety of their units and their FOBs to be with them. Outside of our interpreters and military counterparts, we didn’t know Iraqis or Afghans or even really want to know them. The attitude of Rodriguez in Phil Klay’s “Prayer in the Furnace” is probably closer to the truth for many soldiers: “’The only thing I want to do is kill Iraqis,’” he says. That’s harsh, but the blighted relationships between Americans and Iraqis in Helen Benedict’s Sand Queen and Americans and Afghans in Joydeep Roy-Bhattacharya’s The Watch, marked by mutual hostility and distrust and played out within steps of FOB gates, also seem typical. To venture far outside the wire on one’s own was unfathomable.

But maybe Bergdhal was the exception that proves the rule. Maybe he really wanted to be among Afghans without the security of his weapon and squadmates, to see what happened for better or worse. Perhaps he thought there were good Afghans who would protect him or that the Taliban weren’t really interested or really so bad. Maybe his unit was just so screwed-up and unfriendly that he couldn’t stand it anymore. Or maybe he just got too much a snort of that wild Paktika air, which, as I’ve written about before, has turned other warriors into poets. Did he know Into the Wild, the story of a young man who assumes enormous risk by walking solo into the Alaskan outback? I wouldn’t be surprised.

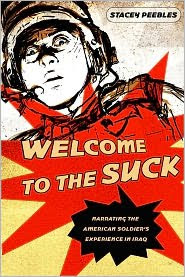

As for me, I’m currently reading Stacey Peebles’ Welcome to the Suck: Narrating the American Soldier’s Experience in Iraq, a study of contemporary war lit written by veterans up to about 2010. I’m only about 30 pages in, but am already impressed by Peebles’ insights about modern soldiers and how they represent themselves in memoirs, stories, and poetry. Peebles claims that the dominant theme in contemporary war lit is the desire of veteran-authors to transcend their identities as soldiers. Raised in a culture that now values diversity above almost all else, military men and women resist homogenous absorption by the martial world they have entered. And yet, Peebles continues, the anguish that fills the best books stems from the military’s way of imposing itself comprehensively on people’s sense of themselves. If not the uniforms and regulations, then the culture and the unit, or the demands of accomplishing missions. If not the mission, then fear, pain, and death. If not fear, pain, and death, then responsibility for what one has witnessed and done. As military identities and mindsets harden, they blot out memories of past lives and other selves, delimit possibilities for relationships in the present, and extinguish potential future options. It then becomes a question not of “being all you can be,” as the Army slogan would have it, but the military becoming all that you can be. Forget the divide between those who have served and those who have not, Peebles says, the real civil-military divide is within the psyches of soldiers and veterans:

As for me, I’m currently reading Stacey Peebles’ Welcome to the Suck: Narrating the American Soldier’s Experience in Iraq, a study of contemporary war lit written by veterans up to about 2010. I’m only about 30 pages in, but am already impressed by Peebles’ insights about modern soldiers and how they represent themselves in memoirs, stories, and poetry. Peebles claims that the dominant theme in contemporary war lit is the desire of veteran-authors to transcend their identities as soldiers. Raised in a culture that now values diversity above almost all else, military men and women resist homogenous absorption by the martial world they have entered. And yet, Peebles continues, the anguish that fills the best books stems from the military’s way of imposing itself comprehensively on people’s sense of themselves. If not the uniforms and regulations, then the culture and the unit, or the demands of accomplishing missions. If not the mission, then fear, pain, and death. If not fear, pain, and death, then responsibility for what one has witnessed and done. As military identities and mindsets harden, they blot out memories of past lives and other selves, delimit possibilities for relationships in the present, and extinguish potential future options. It then becomes a question not of “being all you can be,” as the Army slogan would have it, but the military becoming all that you can be. Forget the divide between those who have served and those who have not, Peebles says, the real civil-military divide is within the psyches of soldiers and veterans:

“As young people, these soldiers have been encouraged to revel in their individuality, challenge restrictive categories, and make ample use of technology to do so. Contemporary American culture traffics in identities that are cyborg, hybrid, avatar…. The media savvy and extensive knowledge of pop culture, however, is anything but a balm for the realities of war, and only exacerbates their sense of isolation and impotence.”

“Other soldiers express dissatisfaction with traditional gender roles, most notably the dictates of masculinity, but their attempts to construct a viable alternative fail. Some arrive in Iraq ready to reach across national and ethnic divides and make a difference, but the invasion’s execution prohibits them from doing so, reinforcing their sense of being strangers in a strange land. Finally, traumatized and injured veterans find that after such radical changes to the mind and body, the most sophisticated treatment and technology in the world can’t always make them whole again.”

“[In contrast to soldiers in Vietnam War fiction] soldiers in these new war stories also feel betrayed—not necessarily by their nation, which many already believe is on a fool’s errand in Iraq, but by the personal resources they expect to carry them through. They are politically cynical, but personally idealistic, believing themselves to be beyond the strict categories of race and gender, to be technologically and culturally savvy. But these resources fail them as well… In war, the realities of biology, physics, and psychology can hit home with a vengeance—and there’s no way to log off.”

Peebles’ body of evidence is slim: Jarhead, My War, Here, Bullet, The Hurt Locker, and a few others. But there wasn’t much to work with as she wrote, so I think she has done well mining what was there for exciting discoveries. An interesting project would be to size up her conclusions in regard to the many novels about Iraq and Afghanistan that have emerged since she completed her study. Do Peebles’ ideas hold true for The Yellow Birds’ John Bartle? Billy Lynn of Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk? Fobbit’s Abe Shrinkle? Sparta’s Conrad Farrell? Or, turning back to real life, how about Bowe Bergdahl, who grew up a writer of metaphysical manifestos and fan of Ayn Rand, who then found himself a soldier soldiering not just at the front, but in front of the front on the Pakistan border. At some point he just didn’t want to do that, or be that, anymore.

Here’s to a full physical, mental, and emotional recovery for Bowe Bergdahl and to a successful reunion with his parents. We look forward to learning much more about the facts of his disappearance and captivity.

Stacey Peebles’ Welcome to the Suck: Narrating the American Soldier’s Experience in Iraq. Cornell University Press, 2011.

Note: An earlier version of this post linked to a blog post purporting to describe Bergdahl’s World of Warcraft fascination. That post is in fact a fabrication, though a very inspired one at that. The influence of role-playing games in the lives of modern soldiers and the art that represents them is a subject for another day.

This is the most thoughtful read on Bergdahl I have yet to encounter. Thank you, LTC Molin. I have been troubled that so many insiders and civilians are so unhappy with Bergdahl, and any repercussions his actions may have had. I can’t argue with their feelings or experience, but it has been frustrating and confusing in the sense that one wants to feel joyous and relieved when an American POW is returned no matter what the circumstances.

Thanks, Lisa. The military justice wheels will spin as they will, but the interesting things to look forward to are Bergdahl’s own account of his disappearance and captivity, and whether he and his squadmates have any interest in reconciliation. I’d place a lot of stock in his peers’ and immediate chain-of–command’s acceptance or rejection of him. A basic question is whether they have any desire to talk to him again or not.

I am a researcher in the literature of modern Iraqi, I would like a comparative research between the novels of U.S. and Iraqi forces have been written on the subject of the war in Iraq, we have in Iraq, more than 450 novel written after the events of 2003, I talked about the war in all its aspects, and I chose three axes of the search; first is life translators working with the U.S. military, and the second is the theft of Iraqi antiquities from the Iraqi Museum, and the third is the return of Iraqi expatriates to their homeland after the change, these topics I wrote about the Iraqi novels, I want to help choose an American novels written about the same topics , One hundred and one nighits – Fobbit – Baghdad central – Cannonball …. Please help me in this matter, and if someone can join me in the writing of this study, and will be a partner with me in the research or writing a book that I hope ….

Karem, thank you for your interest in this subject. Siobhan Fallon’s story “Camp Liberty” in You Know When the Men Are Gone and Phil Klay’s story “Money as a Weapons System” in Redeployment both feature Iraqi interpreters. I’ll write you an email privately to explore other ways I might help.

Dear thank your attention, I’d like to tell you that I worked on currently collecting the novels of Iraq issued after the events of 2003, and I’m trying to be classified, and I’m interested in specific topics, such as:

1 suffering of the Christian community in Iraq, the events of 2003, and here I found that the novel (st.Peters Bones-Kenneth R.Timmerman)) talk about this topic

2 Iraqi expatriates return to their homeland after the fall of Saddam Hussein, and here I found a novel (one hundred and one nighit – Benjamin buchholz)

3 suffering translators working with U.S. forces, I can not find a novel talking about this topic

4 theft of Iraqi antiquities after the events of 2003, especially the looting of the Iraqi Museum, I did not find a novel talking about this topic