A flutter of recent data points raise the questions whether veterans are natural storytellers and whether they are prone to adorn their stories to impress listeners. An article by “Angry Staff Officer” on the Task and Purpose website titled “Three Things That Make Service Members Great Storytellers” asserts that the combination of “mission, story, and time” allows men and women in uniform to “relate our cultural and personal experiences to a group, bring them into the story in an intimate setting, and reveal a shared identity.” Angry Staff Officer cites soldiers from the South as military tale-tellers par excellence, a notion corroborated in “Colleen,” from Odie Lindsey’s fine collection of stories about Southern veterans of the Gulf War and Operation Iraqi Freedom titled We Come to Our Senses. The narrator sets a scene in a VFW hall:

A couple of men asked Van Dorn how he was, and he held court as he blustered and bragged. They tolerated this, because storytelling—his or anyone’s—cued up the opportunity to indulge their own tales, to again revisit their trauma.

So the men did just that, they ran a story cycle, memory to memory, barstool to barstool, and on down to Colleen.

But it’s not just service members from below the Mason-Dixon Line. Last week, at a family reunion in upstate New York, my cousin’s kid Teddy, who served as an infantryman in Iraq, at a late night campfire related tales that were quite a bit more engaging than anyone else’s. Teddy didn’t speak of war, and he didn’t bluster or brag, but he smoothly turned routine events of his life into stories and the people who populated them into personalities. Like Angry Staff Officer describes in his post, as I listened to Teddy it was as if I was once more in an MRAP on a long conop in Afghanistan, eavesdropping through earphones to the crew members spin tales about past missions, past assignments, and past lives.

While Angry Staff Officer writes of how service members and veterans communicate among themselves, David Chrisinger explores how and why veterans frequently embellish the stories they tell or write for civilians. In a piece titled “The Redemptive Power of Lying” posted on Warhorse, Chrisinger writes, “I’m OK with lies—the ones my students need to tell themselves, and in turn, tell me—but I’m not OK with bullshit.” Matt Gallagher, who always has something good to say in these cases, picks up on Chrisinger’s theme. In a recent story published in Playboy titled “Babylon,” Gallagher has his protagonist, a female USMC vet living in Brooklyn, state:

Some of the biggest posers I’d known were vets. The pogue who never left Kuwait but needed to pretend he’d crossed the brink. The staff officer whose lone patrol off base became more dangerous with each of her retellings. Even the grunts, it was rare for them to stick to the truth, because the truth was never enough. War stories meant bullshit, that’s just how it was. Deep down, I knew I’d exaggerated what happened that day in Al Hillah to people, be they surly uncles I wanted to impress or lipstick dykes I wanted to screw. I wasn’t proud of it. But still. It’d happened, and it’d probably happen again.

Maybe we’d earned the right to bullshit….

Recently, the popular Humans of New York website and its even more popular Facebook page have been featuring Iraq and Afghanistan vets relating vignettes of intense wartime experiences. The vignettes, or anecdotes, exemplify the tendencies noted by Angry Staff Officer, Chrisinger, and Gallagher: short, well-turned, gripping accounts of extraordinary events experienced by the veterans, accompanied by poignant statements about the events’ lingering significance in their lives. The posts have been shared on Facebook upwards of 10,000 times, and the comments sections have generated hundreds of compliments, denunciations, and other expressions of belief, disbelief, support, and even accusations that the veterans’ stories were fictive.

If the Humans of New York posts offer a glimpse of the contemporary war-story-telling zeitgeist, the lessons are simple: 1) Go sensational. 2) Go emotional. 3) Keep your own experience at the center, and 4) Convey conviction that your perspective of the event you describe is the true one. Don’t mince around; what people want to hear about is either the worst thing that ever happened to you or the most triumphant. The worst thing is always the shock of learning that war is much worse than you could have imagined or can handle. The best thing is always that you acquitted yourself well in combat.

If you can’t hit those notes, well OK, but be ready for a less-than-enthusiastic response from the reading masses. Tell a subtle, nuanced tale reflecting perplexed anxiety about things that you observed while you were in the military, and five, 500, or 5,000 people might be interested. Tell a graphic story of harrowing adventure and personal tumult, and your audience will be 50,000, 500,000, five million, or more. Edgar Allan Poe wrote long ago, “But the simple truth is, that the writer who aims at impressing the people, is always wrong when he fails in forcing that people to receive the impression.” The lineaments of war story popular connection are right there for the taking. Hint—they look a lot like American Sniper. Reading suggestion—another story in Lindsey’s collection, titled “Chicks,” a funny one about a screenwriter trying to pitch his war-movie script to a producer, brilliantly dramatizes and complicates Poe’s notion. Just in case it’s not obvious–“Chicks” will never be as popular as American Sniper.

Many years ago the French anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss proposed the phrase “the raw and the cooked” to distinguish between primitive and advanced indigenous populations. Lévi-Strauss’s specific subject was food preparation—the move from eating food raw to cooking it clearly demarcated a cultural advance—but lots of critics have since used the phrase to analyze all kinds of human activities, and I’m going to do the same now. War stories, says I, come in two kinds—the raw, visceral kind that use blunt language to describe combat, killing, war brutality, and the rough aspects of military life, and the more mannered and brooding efforts I am calling “the cooked,” which might be described as an attempt to represent a thinking-person’s take on war. Both terms have connotations: when it comes to war writing, “raw” is inevitably linked with “honesty,” which makes “cooked” seem overly-analytical or even evasive. If you’ve eaten twenty straight raw meat-and-potato dinners, however, you might appreciate a little imaginative culinary preparation the next meal around. No doubt, I prefer a literary “cooked” approach, but I’m also in awe of the power of the “raw” to capture the imagination of soldiers, writers, and audiences, so, really, as you work through what I say next, try to avoid thinking of either term as inherently pejorative or complimentary. Instead, consider them as poles on a spectrum of war storytelling possibility.

The great example of contemporary “raw” war-writing is American Sniper. Never mind that Chris Kyle had extensive ghost-writing help, parts of his memoir may have been fabrication, and Kyle himself disavowed aspects of his own story. American Sniper resonated deeply because readers responded to and respected Kyle’s unapologetic and visceral account of his actions in a voice that they identified as authentically his own. Whether it was the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth, or not, it just seemed honest:

I had a job to do as a SEAL: I killed the enemy—an enemy I saw day in and day out plotting to kill my fellow Americans.

The first time you shoot someone, you get a little nervous. You think, can I really shoot this guy? Is it really okay? But after you kill your enemy, you see it’s okay. You say, Great….

I loved what I did. I still do. I don’t regret any of it. I’d do it again.

I never once fought for the Iraqis. I could give a flying fuck about them.

There are many signature elements of a “raw” war story that help register such honesty. One of them is a blunt, hard-boiled prose style, full of profanity and tough talk, as if the author, his narrator, and his characters were really angry about something. Another is unbridled contempt for the chain-of-command; raw war stories bristle with certainty that higher-ups are stupid, vain, and selfish. A third is a thorough self-identification as a soldier or veteran and the assertion of undying brotherhood with fellow soldiers. A fourth is preoccupation with killing and battlefield carnage. A fifth is the treatment of the enemy as savages without humanity or distinction. These signature elements, in my opinion, are diluted in contemporary war writing, American Sniper excepted. If you don’t believe me compare Larry Heinemann’s Vietnam War novel Paco’s Story, which won the National Book Award in 1987, with Phil Klay’s Redeployment, which won the same award for 2014. In terms of the rawness criteria I have established, Paco’s Story rates about a 9 on a scale of 10, while Redeployment gets maybe a 3 or 4. American Sniper is up there with Paco’s Story in terms of rawness, but where Heinemann’s rawness is a stylized literary effect that impressed critics and several thousand readers in its time, Kyle’s memoir has been scorned by critics, while causing the masses to build memorials in his honor.

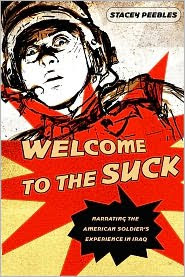

Kyle’s last quote above—about not giving a “flying fuck” about Iraqis—is interesting, because it brings into play something I’d like to propose is true of contemporary war writing. The signature elements of raw war stories may not appear as often in war writing across the board these days, but the fifth still persists as a demarcation point separating war writing into raw and cooked segments. The main ingredient of a “raw” war story about Iraq and Afghanistan, I would say, is lack of interest in or outright contempt for Iraqis and Afghans, while a “cooked” war story manifests curiosity about them, attempts to portray them “as people,” and worries about the cost of war on them. I could without hesitation divide the 20 or more works of fiction I’ve reviewed on Time Now and the countless works I’ve read but have not (yet) reviewed, and rate them based on their empathy for the inhabitants of the land in which the Americans portrayed were fighting. Stacey Peebles also (first, really) hit on this means of evaluation in a chapter in Welcome to the Suck: Narrating the American Soldier’s Experience in Iraq in which she compares Brian Turner’s Here, Bullet and John Crawford’s Iraq War memoir The Last True War Story I’ll Ever Tell. Crawford left Iraq venomously disdainful of Iraqis, while Turner’s surfeit of empathy for Iraqi people, history, and culture threatened to overwhelm his effectiveness as an infantry sergeant. Peebles writes, “If Crawford takes in nothing of Iraq and empties himself out until he is a hollow shell, Turner takes in so much that he is full to bursting.” It follows then that Crawford’s memoir is “raw” and Turner’s poetry is “cooked.”

Which brings us back to the Humans of New York. The names of the veteran story-tellers are not given, but the second and third are both authors about whom I’ve written about on this blog, Jenny Pacanowski and Elliot Ackerman, respectively. Both are savvy writers and in Pacanowski’s case a seasoned performer of spoken-word poetry. In her scathing, ribald, and often extremely funny monologues, Pacanowski presents her tour-of-duty in the Army and Iraq as terrible to the point of traumatizing. Ackerman’s Afghanistan war novel Green on Blue, on the other hand, is practically void of American characters and instead places a Pashtun militia member at its narrative center. According to the schema I have set up, Pacanowski’s poetry is an example of “raw” war writing, while Ackerman’s novel represents the “cooked.” But in their Humans of New York vignettes, we can see them each moving toward a middle ground: Pacanowski fighting to demilitarize her all-consuming self-identification as an angry veteran, Ackerman letting down his guard to let the world take a better measure of who he is as a person. Be sure to read them, and salute to both.