Recent poetry volumes by Hugh Martin, Abby E. Murray, and Nomi Stone reflect the ongoing pull of war and military themes on poets and the authors’ fascination with the poetry as a means of reflecting on their experiences as soldiers, military spouses, and military observers, respectively. “Experience,” it seems to me, is a key word for sussing out the nature of the books’ achievements. I remember a telling Tweet or Facebook post from Lauren Kay Johnson a few years back in which she queried veteran friends and followers about a word that might be used as a synonym or alternative to the word “experience” to categorize their time in the military and on deployment. Responses were mixed, or not especially helpful, as I recall: more evidence that the word might be both overused and under-interrogated as an all-purpose label for how we conceptualize time spent in uniform, at war, or rubbing up against the strange culture of the military in ways that seem interesting, important, or even transformative.

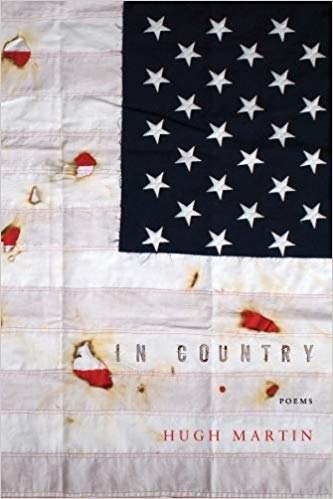

Hugh Martin, In Country

Most of the poems in Hugh Martin’s In Country, as in his first volume, The Stick Soldiers, consist of vignettes of events Martin lived through on his tour in Iraq as an Ohio National Guardsman in 2004. A few poems are set afterwards, and these more directly address what it means to live-on following service on the ground in combat in Iraq. Some, such as the title and title-poem, which reference Bobbie Ann Mason’s great Vietnam novel of the same name, touch on even larger circles of historical-cultural signification. Martin is not given to over-arching pronouncements or editorializing within the space of his poems, however. Instead, he emphasizes observed detail and understated tactics of suggestion and inference. What I get from his poems, and it may not be at all what Martin intended, is a need to document the idea and fact that he, the poet Hugh Martin, in 2018, is the same young man who went to war in 2005 and with a gun strapped to his body did the things war asks soldiers to do–break down doors and shoot people, for starters. The dots connecting the two Hugh Martins go mostly implied or unconnected or too-scary to face directly, which is OK by me, since they go largely unresolved in my own mind in regard to my own deployment and life afterwards, too. So, I can relate to the perceived overall sensibility of In Country, just as I can easily relate to the vignettes of actual deployed experience that Martin captures in verse, such as this one:

“Test Fire”

-south of JalawalaAfter we drive through

the barren hills

where the earth unrollsitself for miles, where the soil’s

as stale as boxed cookies

sent from the YoungstownUSO, the gunners fire

machineguns at the ridge

wall’s face—smalldust-explosions lift

to the sky like faded desert

larks while the rest of usshoot from our knees, our

chests, as copper casings

rain like loose changeacross the dirt, then

as we convoy back

to Cobra from nowherethe Bedouin come

to collect the shells

& stuff them in sacks& after they go: only

boot & footprints,

a careful cursive of tire-tracks.

Abby E. Murray, How to Be Married After Iraq

Many of the poems in Abby E. Murray’s How to Be Married After Iraq reflect the authors’s felt disjunction between her identity as a woman and a poet with an MFA and PhD in literature and her role, or chosen life, as the wife of a career infantry officer. The social milieu of officer marriages, and, speaking from (again) personal knowledge, especially that of infantry officer marriages, is strange and cloistered, so much so that I sense it can be off-putting to observers from the outside. The almost perverse blend of intense competitiveness, ambition, physical vitality, concern for appearances, and homosociality of the men as they are observed by their wives has been ably recounted by Siobhan Fallon in fiction and Angela Ricketts in non-fiction, and part of their accomplishment lies in noting the tension inspired by their own complicity in the experience. Fallon, Ricketts, and now Murray have missed nothing, taken great notes, and, when they are so inclined, punch very hard. The best poems in How to Be Married After Iraq, however, do much more than express ambivalence about military marriage. Murray, much like fellow military-spouse poet Elyse Fenton, is a superb chronicler of the distortions on her own psyche and the nation’s wrought by endless life during wartime, distortions on which her vantage point in the inner-circle of the warrior kingdom gives her exemplary purchase. Here’s the beginning of a Murray poem that begs to be paired with Brian Turner’s “At Lowe’s Home Improvement Center”:

“Sitting in a Simulated Living Space at the Seattle Ikea”

To sit in a simulated living space at Ikea

is to know what sand knows

as it rests inside the oyster.

This is how you might arrange your life

if you were to start from scratch:

a newer, better version of yourself applied

coat by coat, beginning with lamplight

from the simulated living room.

The man who lives here has never killed.

There is no American camouflage drying

over the backs of his kitchen chairs,

no battle studies on the coffee table.

He travels without a weapon,

hangs photographs of the Taj Mahal,

the Eiffel Tower above the sofa.

The woman who lives here has no need

for prescriptions or self-help,

her mirror cabinet holds a pump

for lotion and a rose-colored water glass,

her nightstand is stacked with hardcovers

on Swedish architecture….

And onward to a striking set of closing lines:

you wish you could say this place

is not enough for you, that you’re better off

in the harsh light of the parking garage,

a light that shows your skin beneath your skin,

the color of your past self,

pale in places, flushed in others.

UPDATE: Many of the poems in the chapbook how to be married after Iraq are included in her 2019 Perugia Press publication Hail and Farewell. A review of Hail and Farewell may be forthcoming as I consider the ways it extends and goes beyond the ideas and subjects I’ve discussed here.

Nomi Stone, Kill Class

As a veteran of the Army’s National Training Center, Joint Readiness Training Center, Jungle Operations Training Center, and most valuably, pre-Afghanistan deployment scenario-training at Fort Riley, I for one am fascinated by the idea of a verse volume that takes these places as its subject. Voilá, Nomi Stone in Kill Class has written a series of linked poems inspired by her anthropological field work at several US military training centers that prepare soldiers for Iraq and Afghanistan by putting them through role-playing scenarios staged by émigrés from the war-ravaged regions to which the soldiers will deploy. Stone’s poems are not especially interested in presenting themselves as accessible and easily absorbed, however. Narrative linearity, connective explanations, and summarizing statements are few; instead Stone offers shards, impressions, aggressive line-breaks, non-standard punctuation, abrupt transitions, and oblique references. The intimidating verse surface in Kill Class reflects the complexity of Stone’s background and subject position: educated as a poet in the manner of formidable modern masters such as Jorie Graham and as a Columbia-trained cultural anthropologist, Stone appears to have sometimes or often crossed lines and became a role-player herself named “Gypsy” in the training scenarios, so, like Jen Percy in Demon Camp, she deliberately foregrounds her (un)trustworthiness as an objective observer while at the same time asserting her insider bona-fides. Stone’s critique of war and the military is no more savage than they deserve, and her human sympathies extend almost equally to Muslim role players and American paratroopers, while the complicated poetics mirror the complexities of twenty-first century war, culture, militarism, identity, performativity, and the subjective nature of reality and the elusive processes of meaning-making. Kill Class may not give away its insights cheaply, but readers who invest the time will find much to appreciate about the interpretive experience it summons.

“War Game: Plug and Play”

Wait. Begin Again.

Reverse loop. Enter the stage.

The war scenario has: [vegetable stalls], [roaming animals],

and [people] in it. The people speakthe language of a country we are trying

to make into a kinder country. Some

of the people over there are good /

others evil / others circumstantiallybad / some only want

cash / some just want

their family to not die.

The games says figureout which

are which.

Finally, it’s almost certainly against the reading strategies proposed by Kill Class to read for conventionally “poetic” images, but Stone is quite capable of some stunners, such as the following lines from “War Game: America”:

There is a door in every word;

behind it, someone grieving.

****

Hugh Martin, In Country. BOA, 2018.

Abby E. Murray, How to Be Married After Iraq. Finishing Line Press, 2018.

Nomi Stone, Kill Class. Tupelo Press, 2019.