Good fiction offers exemplary opportunity to consider what Raymond Williams called “structures of feeling”—the mindset and emotional disposition and cognitive frames and processes that are experienced individually as part of a larger collective of similarly-minded people. Two recent works of fiction by veterans excel in their portrait of the structure of feeling of distinct cohorts: Army infantrymen in Afghanistan and young black Americans shaped by war and political conflict.

Adrian Bonenberger, The Disappointed Soldier and Other Stories from War

Adrian Bonenberger’s The Disappointed Soldier is a collection of short-stories that draw on Bonenberger’s two tours in Afghanistan as an Army infantry officer and subsequent malaise in his first few years after service. Far from being rote auto-fiction describing familiar scenes frequently found in contemporary veterans’ writing, the stories draw artistic inspiration from the fanciful, often absurd and satirical, and mostly dark literary fiction Bonenberger enjoyed growing up. As Bonenberger writes in his Introduction, it was in his childhood and adolescent reading that he “first encountered the insane logic of Catch-22, there that I read The Good Soldier and Gulliver’s Travels.” Later, Bonenberger writes, “This collection was written in good faith, for a small but discerning audience in the spirit of a non-literal search for truth.”

The “non-literal” aspect of the stories reveals itself in flights of allegorical fancy that re-arrange realistic details and plausible soldier experience to heighten incongruities and dislocations of American warfaring in Afghanistan and its aftermath. In one story, for example, “The Uniform,” a soldier’s uniform comes to life, serving as the alter-ego or doppelganger to its owner’s civilian identity. Another example is the story “Captain America,” in which an Army officer named John Appleseed America returns to the same geographic locale on multiple tours in Afghanistan. The conceit allows the story to comment on military tactical and strategic success, or lack of, over years of repetitive endeavors to “win” in Afghanistan. Like “The Uniform,” it’s fairly obvious in description but graphic and resonant in execution through Bonenberger’s rendering of physical and emotional detail. In these regards the stories are very literal. It’s said that one of Bonenberger’s heroes, Joseph Heller, didn’t have to make anything up to write Catch-22, he just “had to take good notes.” Bonenberger eschews “nothing-but-the-facts” literary aesthetics as both dull and incapable of rendering the highest and most interesting truths, but Bonenberger has observed much of infantry battalion culture and its byways, as well as the tactics of contemporary warfighting, and he gets more of these specifics into his stories than most.

Connecting everything in The Disappointed Soldier is a sense of what short-story master O. Henry describes as the classic short-story plot: a man (or person) who bets on himself and comes up short. A deep-seated sense of how personal failure is linked to the impossibility of the Afghanistan mission is reflected in the collection’s title story, and many other stories also channel the spirit of the sadder-but-wiser protagonists of Nathaniel Hawthorne’s wonderful tales “Young Goodman Brown,” “Roger Malvin’s Burial,” and “My Kinsman Major Molineux.” Much veteran fiction and memoir reflects its authors’ sense they have been cheated out of honorable, productive, self-affirming deployments by incompetent military leadership and stupid, incoherent missions. Bonenberger’s aware of these things but refuses to give his protagonists a pass: he susses that the more interesting story to tell is of a soldier’s recognition of how their own shortcomings lead to disillusionment, with little room left to blame anyone but themselves. Understanding that military social capital and self-esteem are built out of a house-of-cards in which the four suits are vanity, ambition, self-delusion, and concern for status and appearance, the stories in The Disappointed Soldier dissect this impossible-to-sustain admixture and depict the despair when the cards come tumbling down.

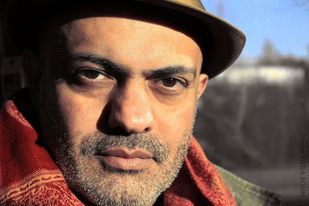

Dewaine Farria, Revolutions of All Colors

The story proper in Dewaine Farria’s novel Revolutions of All Colors recounts the lives of three young black men who come of age in the period from 1995-2005. Putting the men’s exploits and thoughts in perspective is a long first chapter set in New Orleans in 1970 that describes a police crackdown on a local Black Panther chapter, with one of the characters involved a black woman whose job as a city official brings her ideas about black uplift in tension with the much more militant ideas about the same held by the Panthers. The first chapter is terrific: the period-and-place detail thick and rich and the worldviews and personalities of the actors—animated by rage but distinct in their manifestation—vividly described. Not to pour it on too much, but the first chapter reminded me of the fiery fiction and commentary I associate with Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, and James Baldwin, and I leaned forward in anticipation of how Farria would bring his critical and literary acumen to bear on his more contemporary protagonists’ lives and what might be said of race relations in America in the 21st century.

By contrast, however, the interlinked lives of his three modern black Americans—Simon (the son of the woman featured in Chapter One) and brothers Michael and Gabriel are much more placid and unfocused. The young men, from relatively prosperous and stable families, come-of-age in a small Oklahoma town, and while race is never not an issue, the young men seem to feel far less keenly the effects of racism than do their parents, whose constant admonishments that black Americans must never let their guards down seem to lack practical everyday relevance. As the young men explore life possibilities, they appear, frankly, more bemused by white people than at war with them, and just as adrift as many of their young white contemporaries, and they cycle through young-adult career options such as the military, grad school, overseas employment, mixed-martial arts fighting, metropolitan artiste-life, and the like in ways that don’t seem especially tinged by racial hostility and foreclosure of opportunities. All this, I believe, is by design and Farria’s point: he’s describing an interregnum in modern black American life set midway between the Civil Rights/black-militant era and the post-Obama resurgence of much more overt racial tension, when a false calm in the historical storm of American race-relations seemed to prevail and young blacks (perhaps much as Farria himself) struggled to define their relation to the peculiar social-historical circumstances in which they found themselves. Events in Revolutions of All Colors bring the three protagonists to begin a more sustained and mature appraisal of their elders’ lives and ideas, and I can’t help but think that if Farria were to write a sequel that follows his protagonists into the present, their thoughts would grow even more piquant and their actions more consequential.

Farria has served as a Marine and United Nations security advisor in numerous global hotspots, to include Iraq and Afghanistan, and the military and war enter into Revolutions of All Colors not so much in regard to Operations Iraqi and Enduring Freedom but Vietnam and political-social strife in Ukraine and Somalia. One of his protagonists—Simon–serves in Afghanistan as an Air Force pararescueman and later does a stint in Somalia as a security contractor during a period of factional fighting, while other episodes featuring Gabriel are set in Ukraine, where the “Orange Revolution” launched against Russia serves as a backdrop. Simon’s and Gabriel’s thoughts about political violence, however, are cursory in comparison to the weight given in the novel to Vietnam as a crucible of life-forming worldview for many of the Black Panthers described in Chapter One and the father of Michael and Gabriel described in following chapters. For black men who served in Vietnam, a racist military intensified their political awakening while combat inculcated ideas and values about the discipline and training required to fight for one’s rights and stand one’s ground. They also learned to love, or at least appreciate, the thrill of the fight and the sometime necessity of violence, for better or worse in roughly equal measures, though probably mostly better given the precarity and watchfulness required of black life in white-dominated America. This proposition is very interesting to consider, both as it is fuzzily refracted in Simon’s martial inclinations and Gabriel’s and Michael’s lack of the same, and in contemplation of the ways war in Iraq and Afghanistan might shape the outlook of contemporary veterans, both black and white, as they move forward into adulthood.

Adrian Bonenberger, The Disappointed Soldier and Other Stories from War. Kolo, 2021.

Dewaine Farria, Revolutions of All Colors. Syracuse University Press, 2020.

Adrian Bonenberger Benjamin Busch Bill Putnam Brian Castner Brian Turner Brian Van Reet Colby Buzzell David Abrams Drew Pham Elliot Ackerman Elyse Fenton Fire and Forget Hassan Blasim Helen Benedict Hilary Plum Ikram Masmoudi Jehanne Dubrow Jesse Goolsby Johnson Wiley Joydeep Roy-Bhattacharya Kevin Powers Masha Hamilton Matt Gallagher Maurice Decaul Phil Klay Ron Capps Roxana Robinson Roy Scranton Sean Parnell Siobhan Fallon Stacey Peebles Theater of War Tim O'Brien Toni Morrison War art War dance War fiction War film War literature War memoir War photography War poetry War songs War theater Will Mackin