Matt Gallagher’s latest post on the New York Times At War webpage explains the structural fault lines that divide the veterans writing community. Gallagher notes that veterans writing workshops are a growth industry, key components of the veterans programs now established in many colleges and cities. He notes that within the veteran writing community motivations differ. Some see writing as a matter of self-expression or healing. Others see it as a means by which they might turn themselves into big-time, well-regarded artists. Some think their stories need ultra-precise realistic rendering of their personal experiences and are unable to see the need for artistic re-imagining at all. Some veteran writers overvalue the degree to which their war experience makes them uniquely qualified to write about war. They scoff at the pretensions of someone who hasn’t “been there and done that” to write meaningfully and movingly about war.

These are all subjects that interest me. I’m familiar with veterans programs sponsored by colleges as diverse as Farmingdale State and Vassar, to say nothing of my occasional interaction with the veteran population at West Point. It occurs to me that the New GI Bill, which basically funds four years of college for anyone who has recently served overseas, is as worthy a program as the storied GI Bill of the post-World War II days, and that if we as a nation (or at least our government) are serious about our commitment to veterans, generous allotments for education are second only to effective medical care as a material, no-BS way of saying thanks. College is just the right place for many vets—they can simmer down after their service while preparing for their future–and it makes sense that classes that allow them to explore their war experience are part of the curriculum.

The question of whether a writer who hasn’t been to war can write well about war also intrigues me. Gallagher cites Ben Fountain as the example par excellence of an author who never served in the military, let alone saw combat, but who can still convey what it is like to be a soldier. I love Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk, too, but have noted that Fountain evades extended description of battle. Is that a place he just didn’t feel comfortable going? Brian Van Reet, a decorated vet, portrays two horribly mangled veterans in comic-grotesque terms in “Big Two-Hearted Hunting Creek.” Would a civilian feel as comfortable doing so? Is there something wrong with someone who isn’t disabled portraying characters who are? Both these cases reflect the issues of credibility and authority that permeate discussions of war writing.

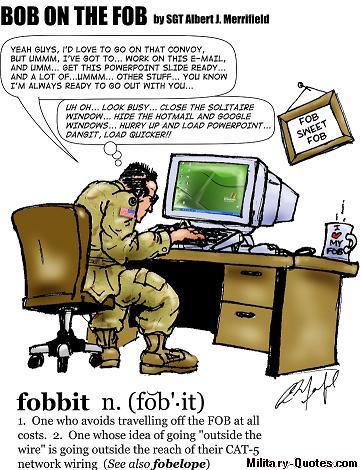

We actually already have lots of fiction and non-fiction that describes what it is like to fight, and what it is like to live after fighting. Most of them are rendered largely through the perspective of one protagonist. I’m eager for a story that expresses the totality of an Iraq or Afghanistan deployment. A cast of characters, not just one main one. A vivid depiction of social milieu, from the squad up to the brigade, as they progress from home station to theater, spend a year on a FOB doing missions while interacting with local nationals, and then redeploy and get on with their post-war lives. A plot that takes a novel to properly set up and unfold. Where is that book? Fobbit, by David Abrams, comes close, but I want more. I’m now starting Sparta, by Roxana Robinson. Robinson’s not a vet, but maybe her book will take me there.

In the meantime, we might consider how a scene might be portrayed through poetry, through fiction, through personal experience. Here is how Brian Turner conveys his thoughts on the plane ride back from Iraq:

“Night in Blue”

At seven thousand feet and looking back, running lights

blacked out under the wings and America waiting,

a year of my life disappears at midnight,

the sky a deep viridian, the houselights below

small as match heads burned down to embers.

Has this year made me a better lover?

Will I understand something of hardship,

of loss, will a lover sense this

in my kiss or touch? What do I know

of redemption or sacrifice, what will I have

to say of the dead — that it was worth it,

that any of it made sense?

I have no words to speak of war.

I never dug the graves of Talafar.

I never held the mother crying in Ramadi.

I never lifted my friend’s body

when they carried him home.

I have only the shadows under the leaves

to take with me, the quiet of the desert,

the low fog of Balad,

orange groves with ice forming on the rinds of fruit.

I have a woman crying in my ear

late at night when the stars go dim,

moonlight and sand as a resonance

of the dust of bones, and nothing more.

And from early in Sparta, here is how Robinson depicts a similar scene:

The plane was full of sprawling, loose-lipped Marines, lost, gone, dead to the world.

Conrad liked seeing them like this: sleep was like salary, his men were owed. They were infantry grunts, and they’d been seven months on duty without a single day off. They deserved to sleep for months, years, decades. They deserved this long, roaring limbo, this deep absence from the world, from themselves. This plane ride was the floating bridge between where they’d been and where they were going—deployment and the rest of their lives. They deserved these hours of unconsciousness, this gorgeous black free fall.

My rendition of the same experience stems from a flight back from Afghanistan on mid-tour leave. I was the senior officer on a charter plane from Kuwait to Ireland. As such I sat up front and conversed with the senior flight attendant. She was maybe 30, with that half-pasty, half-refined look that comes from trying to maintain professional polish while living on hotel room service. She was very nice, and we traded stories while the rest of the plane dozed. Our flight was peaceful, and yet she told me of horrible flights out of Iraq in the bad days of 2006 and 2007, when soldiers would wake screaming out of nightmares born of bad memories and ravaged psyches. Seven hour flights would be filled with noise and bustle as fellow soldiers subdued distraught friends wacked out–or not wacked out enough–on Ambien. As we talked on she told me that she had gone to college at Indiana, as did I. That was cool, so I asked her where she hung out in Bloomington. To my surprise she mentioned the local punk rock club. Judging from her looks and job, I never would have guessed it, but she really knew her stuff. She had run a ‘zine, and still went to shows and knew all the bands. Since I had come-of-age near DC listening to classic hardcore groups such as Minor Threat and the Bad Brains, we had a lot to discuss. So, on through the flight we traded stories about our favorite records and shows. While 90% of the other passengers slept 90% of the time, my interlocutor lured me out of my deployment anxieties and uncertainty about the future with magical tales of a musical history that if we didn’t quite share, we both could appreciate.

My story isn’t as good as Turner’s or Robinson’s, or related as well, but it’s mine, which counts for something. All stories need telling, whether they find many listeners or not. It’s a social catharsis, enacted individually but resonating collectively.

New York Times review of Roxana Robinson’s Sparta

Veteran David Carrell writes about his return to college at Vassar

My War author Colby Buzzell writes about his own love of punk rock