I was invited to give a Veterans Day speech this year at a high school where my friend B___ (also a veteran) teaches. I have never given such a speech before, but I accepted the offer quickly not just out of friendship with B __, but because I was curious to see what the opportunity inspired me to say and how it would go over. The audience was upwards of 500 students and faculty, and as I spoke I couldn’t tell how I was faring, but upon conclusion the audience rose and gave me a long standing ovation, which I didn’t see coming and which moved me enormously.

Below’s the speech, for anyone who is interested. It’s ten-minutes long and tempered for an audience of high-schoolers with little exposure to the military, so not all that I think and could say about the subject. I’ve also resisted the urge to tidy it up after-the-fact or revise it to include all the great lines I wish I had written beforehand but didn’t think of in time.

****

Hello everyone, and thank you for inviting me to speak at P___’s Veterans Day ceremony. This is my third visit to P___, all courtesy of B___, and everything I’ve seen has really impressed me. The facilities, the sense of community, the commitment to excellence, and the quality of the faculty and most of all the quality of students strike me as exceptional.

In the time given me, I hope most of all not to bore you. I want to say something original and hopefully entertaining, or at least interesting, about what it means to be a military veteran and how you might honor veterans on the day given to their celebration.

That’s not exactly easy, since the import of Veterans Day is well-established and not hard to understand: the nation has decided that it is right to dedicate at least one day of the year to honoring the men and women who have volunteered to serve in the Armed Forces. Though not all veterans have fought in war, all have chosen to step out of the normal paths of American life at least for a few years to defend the country and, if asked, put themselves in harm’s way. And then, when those few years are done, to become veterans, a new-found identity they will bear with them the rest of their lives.

For me, I became a veteran in January, 2015. For the previous 28 years I had woken up in the morning as a member of the Army, and now I didn’t. For 28 years my wife and two sons had known me as an Army officer, now I wasn’t that anymore, but it wasn’t clear what or who I would now be. For the previous 28 years, the horizon of my life was the next unit, the next deployment, the next promotion. Now, the future was uncertain, and rather than being given to me, it had to be created by myself.

It is this transition from the Army culture and system to that of civilian that is difficult and which turns former military members into veterans.

At first, my new-found identity as a veteran did not feel comfortable. The label felt awkward like a new suit I was not yet used to. For me the publicly visible veterans I knew and saw were old men who had fought in World War II, Korea, and Vietnam. They wore ball caps with unit insignias on them, and often old fatigue jackets. They seemed to care a lot about memorials in Washington, DC, and parades on Veterans Day.

Honestly they seemed to be eager for recognition and approval, which was the exact opposite of how I felt I in January 2015. I wanted to distance myself from my military identity as quickly as possible. I didn’t want to be thanked for my service. I didn’t want to deal with the Veterans Administration. I didn’t want to march in parades and stand up and be recognized at sports events. I didn’t associate much with other vets, nor did I seek employment that traded on my veteran identity. I put the uniform I’m wearing now in the closet and never brought it out for years.

Why was this? Was I ashamed? Did I have regrets? Did I feel like I was tainted by having lived for so long in an organization and culture that was far too familiar, even comfortable with violence and the use of force and the rigid stratification of military hierarchy? Or, was I excited about new possibilities and new ventures? I think most of all I was unsure of how to be a vet. I didn’t know how to manage my thoughts, or the presentation of myself. I worried that I might actually seem too proud of my veteran identity? I was afraid of coming on too strong to civilians, and so I probably overcorrected by suppressing my veteran status and characteristics.

In time, I have become much more comfortable about being a veteran. The transition was enabled by my developing sense of how the military informed me in a positive way, and that the positive attributes of being a military member could carry over into the civilian world. One thing that helped the process was learning to interact casually with civilians—to put them at ease while also defusing anxiety on my part.

Beyond the official hullabloo of honoring veterans on Veteran’s Day is an underlying sentiment of saying, “Thank you for your service.” That sentiment, even as sincerely rendered, can seem inadequate to both service-members and the people saying it. It seems a little undernourished, even trite, incapable of opening up the full range of things that might be expressed. Some veterans report actively disliking being told that. What underlies the discomfort?

From a veteran’s perspective, the idea of being “thanked” doesn’t seem like enough, or even the point. Veterans join the military voluntarily, and they often do so for the pay and the benefits or other personal reasons. When I joined, swirling in my head were the chances for a work-life spent outdoors and dedicated to vigorous physical exercise. Many soldiers join because of familiarity with the military based on having family members already in; it may be something of a family tradition to serve. Some join to get out of unwelcome hometown and family situations—that happens. Others are curious about the chance to experience a life and culture very much outside the typical and “normal” life patterns available to young Americans. That idea honestly was prominent in my own initial decision to join.

The idea of “service” lurked deeper in my awareness. In my mind, for example, was a vague notion that if one loved their country one should “serve” their country, and as a young person with not much to offer, willingness to do so through physically demanding and perhaps dangerous endeavor was appealing. Even as I thought that, though, it was clear to me that there are many ways to serve the country; for example, service is embedded in the idea and actuality of going to school, getting an education, and finding a job or career: we are all in one way or not serving in ways that contribute to a better community and nation. And so, the idea that I should be thanked for joining didn’t cross my mind and would have felt strange if someone had broached it. To me, I was thankful that such an opportunity that married so nicely with my own interests and desires existed. And so, I often respond to the expression of saying, “Thank YOU for supporting me,” or “Thank YOU for YOUR service.”

Still, “Thank you for your service” is the phrase we have, and I try not to be critical or overly analytical about it. But built into the conundrum of “Thank you for your service” is the difficulty of understanding what else might be said, or what might be said next. At heart, is the idea that any further questions might take the conversation to a dark place or an overheated political place. Not more really needs to be said, in many or most cases, but here are some ideas that balance tact with sincere curiosity.

First off, ask a veteran what branch of the military they were in—Army, Navy, Air Force, Marines, or Coast Guard—and why they joined. For me, it was the Army, because it seemed the most representative of American history and experience. Just as much, I wanted to go to Ranger School, which only the Army offered.

Ask a veteran WHERE he or she served. There’s not a lot of judgment involved in such a question, and as the military rarely fails in sending service members to interesting or exotic places and veterans generally like to recount their travelogues. For me, I would say, lots of places: Missouri, Georgia, North Carolina, Kansas, New York, and New Jersey in the United States, and Korea, Panama, Egypt, Kosovo, and Afghanistan overseas. You might then say, “Which one did you like best? Or, “What was such-and-such a place like?” It’s an expression of curiosity and personal interest, and you are likely to get an interesting response tempered to be light or even amusing. The veteran may be moved to tell you about a place he or she didn’t like, but rarely will the veteran use such a prompt to make you feel uncomfortable.

Or, you might ask, “What did you do?” Most veterans will take this as a question about their job, and will reply in terms in regard to what is known as their “Military Occupational Specialty.” In the Army that can range from infantry to cook to medic to tanker to truck driver to administrative clerk. The other branches have an equally wide range of jobs, many of them more exciting than anything the Army offers. Again, a simple, “How was that?” will probably elicit a good-natured anecdote or two. It’s a light, friendly gambit, but you will learn something, and the veteran will use it to measure whether the time and place is right to burden you with anything too detailed or heavier, which he or she will probably decide it is not. But the groundwork has been laid for such a conversation in the future, if the situation is right.

Lurking behind these opening pleasantries are more profound questions, chief among them “Did you see combat?” and its evil twin, “Did you kill anyone?” The “Did you see combat?” question is natural. If the veteran did see combat, the answer is likely to be, “Yes, a little,” or “Yes, a lot” and honestly will probably want to leave it at that. If the veteran did not see combat, the answer will be “No, I never did” or maybe “Thank God, I never did” and similarly, leave it at that for the time being. I don’t recommend asking the “Did you kill anyone?” question, though, frankly, it is often asked, especially by young people. If the answer is “no,” the veteran is apt to shrug it off, perhaps with a laugh, and say, “No, I never had to do that.” If the answer is “yes,” the conversation has reached a difficult place. The answer is likely to be measured, as the veteran weighs the tone and amount of detail the response requires. For me, the answer would be, “No I never personally did, but the soldiers I led certainly did, and I gave the orders that sent them into battle.” If the next question is “How did you feel about it then and how do you feel about it now?” my answer would be, “The situation demanded it: it was kill or be killed, and I would have given any order required to protect my soldiers while also ensuring they could live with themselves afterward.”

And so, now we are on to the larger, consequential questions concerning politics and morality. The rules of civil adult-to-adult conversation now apply, and the groundwork has been done that the veteran is likely to feel comfortable expressing their views. The talk is likely to go anywhere and so be it, as long as the spirit of respect and care apply.

You might also ask the veteran questions related to being a veteran, such as:

“What are you doing now?” Me, I’m teaching, which I see as on a continuum with military service. The transition was aided by becoming a teacher. Teaching, in its ideal form and aspirations, is far different than being in the military, of course. But the military ethos also values near constant education, training, and instruction, the continual effort to master new skills and monitor and supervise the development of those skills in subordinates. In teaching I found the same sense of commitment to improvement that is a hallmark of the military. In joining the ranks of teachers at R____, I found the same sense of pride in belonging to and contributing to a top-notch institution as I did in the best military units I belonged to. I am sure this is true of B____, too.

“What did you learn in the military that is helpful to you now?” Lots of things, but most of all an instinctual or reflexive commitment to team and organizational success. A perceptive civilian friend once told me that the quality she recognizes instantly in veterans is their quickness, as she put it, to say “yes to the group.” By this she meant that veterans are not subservient dupes to group think and leadership authority. Rather, they are quick to recognize that group efforts require enthusiastic buy-in from group members. Veterans, trained to think first of the needs of the unit and mission, she said, rarely hesitate or hold-out. Rather they quickly try to figure out how they can contribute to the success of the group project and the team mission. I trust you recognize this quality in B___, and I hope it’s true for me, too.

“What did you like best about the military?” For me, I often say the military never reneged on its promise of travel, adventure, and camaraderie, and that’s what kept me in for 28 years. I can also say that I never had a bad boss, or at least a really bad one. Rather, the opposite: my bosses mostly struck me as talented-and-good men and women trying their best to accomplish missions, take care of their soldiers, and uphold Army ideals. The same was true of the overwhelming majority of my fellow officers and soldiers. And far from being drags to be around, my bosses were often colorful and inspirational. They made missions seem worth doing by providing purpose and guidance, and as best they could given the circumstances (not always possible) fun, entertaining, or at least interesting. I’ll bet that’s true of B____ as well.

I know there are exceptions to these ideals, and the exceptions bring unwanted attention to veterans and the military. But exceptions are not the rule, and my first and abiding impression of anyone who has served is that he or she really really really wants to do the right thing in the right way. I think that sentiment is felt by most members of the general public and it underlies the spirit of Veterans Day and “Thank You for Your Service.” I’ll leave it at that for now. I hope I have rendered a sense of what it’s like for at least one veteran, and if you trust me, a lot more as well. Thank you for thanking me for my service, and thank you for everything you do, all of you, every day. Go P___!

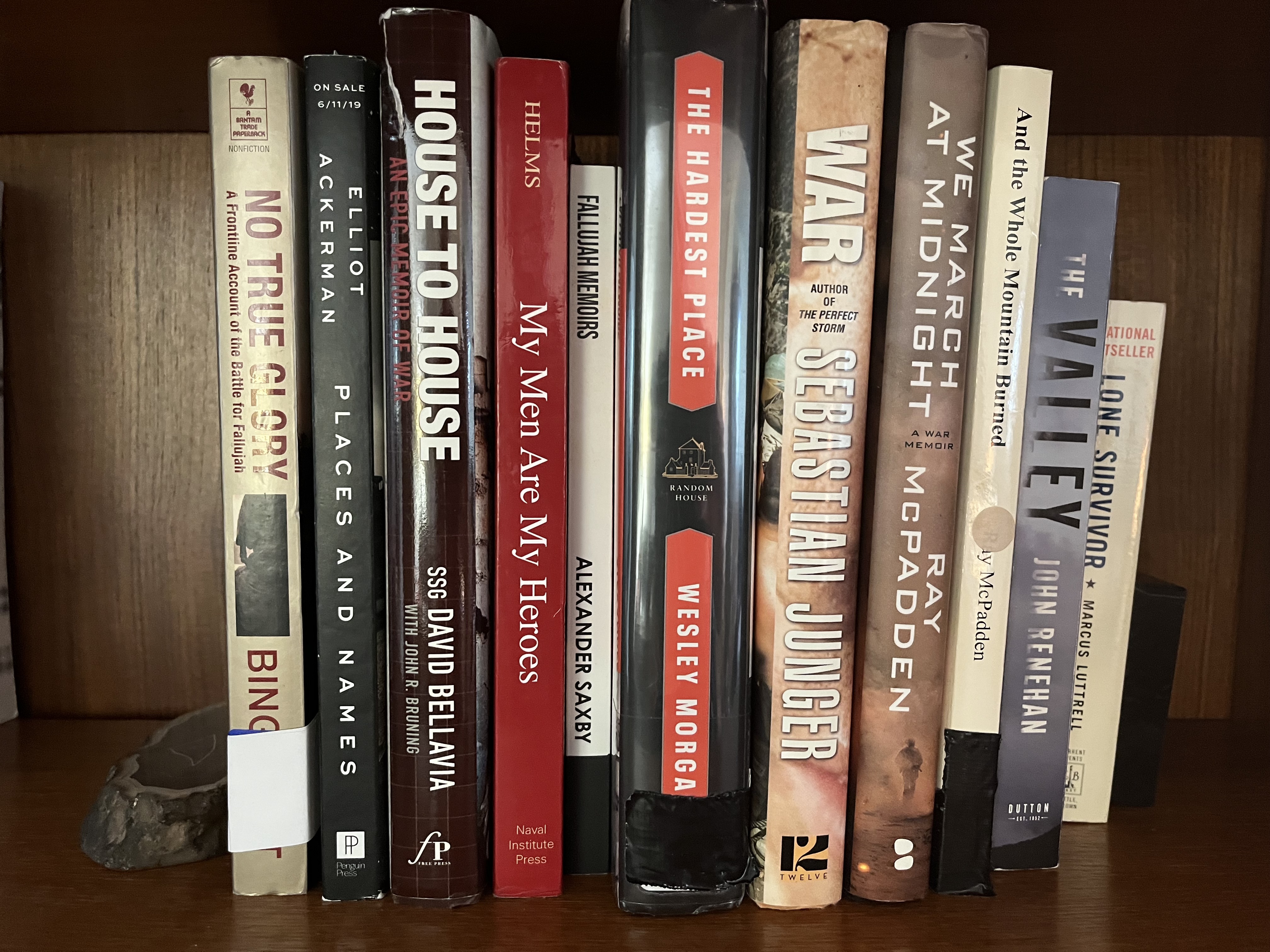

This month for The Wrath-Bearing Tree I’ve written on a subject in which I’ve long been interested: the lifespan of public popularity and critical acclaim of newly-published books and movies in the days, weeks, months, and years after their release. Everyone has an informal sense of how these things go. Some books are acclaimed immediately, but their reputations fade over time. Others are unnoticed upon release, but gain popularity and acclaim in later years. Some are pronounced great early on and attain and maintain “classic” status afterwards. Sometimes an idea, or passage, or character contained in a prose-work or film retains resonance, even as the original work is more-or-less forgotten.

This month for The Wrath-Bearing Tree I’ve written on a subject in which I’ve long been interested: the lifespan of public popularity and critical acclaim of newly-published books and movies in the days, weeks, months, and years after their release. Everyone has an informal sense of how these things go. Some books are acclaimed immediately, but their reputations fade over time. Others are unnoticed upon release, but gain popularity and acclaim in later years. Some are pronounced great early on and attain and maintain “classic” status afterwards. Sometimes an idea, or passage, or character contained in a prose-work or film retains resonance, even as the original work is more-or-less forgotten.