War Photos: Bill Putnam’s Sleepers

A few posts back I wrote about soldiers dozing, or sitting silently and thinking, on their flights back to the United States after deployment. I asked photographer Bill Putnam for a picture to accompany the piece, but Bill was busy and didn’t send me anything until a few days ago. The photos he finally delivered weren’t of a flight home, but of soldiers sleeping and hanging out in their dark hootches while on an outpost in Paktika province, Afghanistan. They immediately sent me into a reverie of memory and association, not just of my own deployment, but of a great Walt Whitman poem called “The Sleepers.”

First published in 1855, “The Sleepers” begins:

I wander all night in my vision,

Stepping with light feet . . . . swiftly and noiselessly

stepping and stopping,

Bending with open eyes over the shut eyes of sleepers

The poet then describes a freak show of damaged sleeping bodies that include…

The gashed bodies on battlefields, the insane in their strong-doored

rooms, the sacred idiots,

The newborn emerging from gates and the dying emerging

from gates

The poet tells us, “The night pervades them and enfolds them” and soon the journey becomes not just physical and literal but symbolic and visionary and the poet doesn’t just describe but inhabits the bodies of the sleepers.

I go from bedside to bedside . . . . I sleep close with the

other sleepers, each in turn;

I dream in my dream all the dreams of the other dreamers,

And I become the other dreamers.

I am a dance . . . . Play up there! the fit is whirling me fast.

Soon to come are passages featuring Lucifer, George Washington, a red squaw Indian, and lots of sexual coupling and release. A smart critic writes:

“In ‘The Sleepers’ Whitman dramatizes a dream vision or psychological journey in which he penetrates a realm of existence–both within himself and in the world–that transcends time and space and finite human limits. . . . Through his dream the poet confronts the chaos and confusion of the mind and the facts of suffering and death. He discovers spirit, as well, and thereby comes to know the possibilities for human life. He possesses all of existence through his vision. . . .”

That makes sense, a little, of a crazy-but-wonderful poem. Please check it out in its entirety and let me know what you think. My favorite lines come near the end:

I swear they are all beautiful,

Every one that sleeps is beautiful . . . . every thing in the

dim night is beautiful,

The wildest and bloodiest is over and all is peace.

Which brings us back to Bill Putnam’s pictures of the dark, sleepy in-between times of a combat tour. I hope you enjoy them as much as I do.

A daysleeper:

And, finally, a sleeper in a transient barracks:

More Bill Putnam photos here.

The critic quoted above is E. Fred Carlisle. His comments on “The Sleepers” and those of other critics can be found here.

Class War: Roxana Robinson’s Sparta

Several good books about the contemporary wars have been written by graduates of an ingenious program that opens up United States Marine Corps Officer Candidate School to rising college seniors, with no obligation for candidates to serve even after they graduate from college. Most do, though, and so the open-armed, non-binding invitation has reaped the Marines a bounty of smart, literary-minded young men from elite colleges who desire a healthy helping of “Semper-Fi Do-or-Die” before getting on with their lives. Among the books written by such men are the memoirs Dust to Dust by Vassar grad Benjamin Busch, Joker One by Princeton grad Donovan Campbell, and One Bullet Away by Dartmouth grad Nathaniel Fink. Coming soon is Redeployment, a collection of short stories by Phil Klay, another Dartmouth grad.

Several good books about the contemporary wars have been written by graduates of an ingenious program that opens up United States Marine Corps Officer Candidate School to rising college seniors, with no obligation for candidates to serve even after they graduate from college. Most do, though, and so the open-armed, non-binding invitation has reaped the Marines a bounty of smart, literary-minded young men from elite colleges who desire a healthy helping of “Semper-Fi Do-or-Die” before getting on with their lives. Among the books written by such men are the memoirs Dust to Dust by Vassar grad Benjamin Busch, Joker One by Princeton grad Donovan Campbell, and One Bullet Away by Dartmouth grad Nathaniel Fink. Coming soon is Redeployment, a collection of short stories by Phil Klay, another Dartmouth grad.

Speaking as a UC-Berkeley grad who went to Army OCS to become an infantry officer, I can kind of relate.

Also taking note of this phenomenon is Sparta, a novel by civilian author Roxana Robinson. Her protagonist is Conrad Farrell, a Williams College graduate from a comfy Westchester County, New York, far-suburban home, the kind whose dirt-road remoteness signals privilege, not poverty. Conrad’s decision to attend Marine OCS shocks and dismays his family and girlfriend. Now back from two savage tours in Iraq and out of the service, he begins a slow but steady deterioration from the ravages of post-traumatic stress.

It’s not a pretty tale, and it’s not told in a pretty, artful way. Sparta is sort of an anti-The Yellow Birds. It relates a similar tale of downward decline, but with none of The Yellow Birds’ lyrical flights (no pun intended) or near as much plot. Episodes unfold schematically: first, impulsive and reckless anger, then apathy and lack of focus, then withdrawal and denial, next headaches and insomnia. Flashbacks and erectile dysfunction. A futile stab at counseling. Alcohol abuse and self-medication. Suicidal thoughts, then suicidal gestures. When Conrad hears a loud bang, you know he’s going to duck. When a car veers too close while he’s driving, you know he’s going to panic. Conrad’s behavior is so out of kilter that it is hard to believe his girlfriend stays with him for a minute, let alone a year. It’s difficult to imagine him as an effective officer, or a cheerful, intelligent guy before he joined. The story is told almost entirely through Conrad’s eyes, but there’s so much we don’t understand. We’re left wondering, for example, why he got out of the Marines, since he has no plan for the future and misses his men so much. Why not get a job to keep busy? Date or chase girls? His depression socks in before he even knows he’s depressed, which might be the nature of such things, but his aimlessness makes him seem more like a goofy man-child than a focused adult. And because we aren’t allowed to eavesdrop on the other characters’ conversations and thoughts, we lose not just their perspectives on Conrad, but a fuller rendering of the angst those close to him must have suffered while hoping that he would once more be OK.

For all that Sparta’s darn near impossible to put down. Because Robinson doesn’t waste a word describing Conrad’s quick step toward self-destruction, Sparta reads very quickly. The prose style is very direct—I can’t imagine a novel that begins as many sentences with “He,” as in the following passage describing Conrad in the process of bolo-ing the GMAT:

He was screwing it up. It was getting worse. He couldn’t pound the little things into any kind of sense. It was getting worse, and the worse he felt, the worse he did. He was in a long panicked slide backward. He could feel himself his going and couldn’t stop himself.

Conrad’s upper-crust stiffness combined with the USMC suck-it-up ethos leaves him not strong but emotionally brittle, and Robinson describes this toxic psychic predicament shrewdly in short, sharp strokes. The most extended descriptions of anything are of the habits and habitats of Conrad’s liberal East Coast native milieu. The references to GMATs, Volvos, maids, and commuter trains remind us that Robinson is not telling a general story about all damaged veterans, but a particular one about a member of a class whose disdain for the war and the military seems based as much on taste and lifestyle as politics. Conrad’s parents care about him, but they take little pride for his service, understandable given his downward spiral, but they also seem to lack the warmth, curiosity, empathy, or other means, to include vocabulary and courage, to connect with him. They are good people in their way, but they are at a loss, and their scorn for soldiering contributes to Conrad’s funk and may even be the cause of it. It’s hard not to think that one thing that really eats at Conrad—in addition to everything else–is his inability to admit that his decision to join the Marines was an act of class betrayal, a big huge self-inflicted mistake, that his parents were right, and that he had every reason to know better.

Roxana Robinson, Sparta. Picador, 2014.

Where’s the War in Contemporary War Novels?

The past few weeks brought two significant additions to the contemporary war literature conversation. The first was a long review essay by Michael Lokesson in the Los Angeles Review of Books called “Passive Aggression: Recent War Novels.” Lokesson’s review covers much the same ground as this blog, with extended commentaries on Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk, Fobbit, The Yellow Birds, and Sparta, among others. Lokesson also offers some historical musing about war and literature, going back to Homer, and finally a bit of meta-analysis on the possibilities for contemporary war lit to achieve greatness. “Reading this latest crop of accomplished soldier’s novels,” he writes, “I couldn’t shake the feeling that maybe modern war and its aftermath, as told through a soldier’s eyes, simply isn’t the stuff of great novels anymore.” Contemplating the fact that much “combat” in Iraq and Afghanistan consisted of waiting for IEDs to go off or a rocket to hit the FOB, Lokesson continues:

“In warfare [today], the soldier is passive to a startling degree, and even the war effort itself is built on passively securing the population rather than actively defeating the enemy. Molding passivity into great literature is never easy, as the current harvest of soldier’s novels attests, and the novelist who sets him or herself to the task is forced to climb a very steep mountain indeed. Can a truly classic novel arise under such conditions? I’d like to say yes, but I have my doubts.”

Regarding the wars that gave us Fallujah and COP Keating, I’m not so sure Lokesson’s characterization of them is entirely correct, though he might be onto something regarding their literature. He seems to have it in mind that a great war novel must portray heroic action or striking scenes of battle, and the current war lit record is scant on both counts. To help stir the pot of discussion, also out recently is Men in Black, a stunning video rendition of a terrific combat scene from Colby Buzzell’s memoir My War. I’ve praised Buzzell’s writing before; for my money, the scenes describing combat in My War render the material detail and visceral feel–half adrenaline, half fear–better than anything I’ve read elsewhere, fact or fiction. Hat’s off too to Buzzell’s collaborator Evan Parsons for bringing My War to video-digital life with his excellent graphic-novel like illustrations. Buzzell is certainly not passive, as either a fighter and writer, which is good, but he’s also not especially reflective. From his grunt’s eye perspective, war is about kill-or-be-killed, with factors that might require thought before, during, or after action of second import. Nor does he portray himself or anyone else heroically.

A great battle scene that unabashedly depicts a war hero can be found in another memoir, Lone Survivor, written by Navy SEAL Marcus Luttrell with the assistance of novelist Patrick Robinson. If you haven’t read the scene lately, or at all, describing the death of Lieutenant Michael Murphy, please check it out. The description of the battle leading up to Murphy’s death is also terrific, with Luttrell and Robinson vividly portraying the terror that comes from being shot at from all sides. While Buzzell’s as irreverent as they come, Luttrell’s 180 degrees the opposite—Lone Survivor is a glowing elegy to an officer whose last moments inspired Luttrell to write, “If they build a memorial to him as high as the Empire State Building, it won’t ever be high enough for me.” The passage gives me the shivers every time I read it, but it’s such an uncomplicated encomium I couldn’t imagine it in a “serious” novel, full of doubt and irony.

So, My War and Lone Survivor demarcate a range of possibilities, but they are memoirs, not fiction. In the major novels, there’s not much combat on display, let alone brave acts. Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk contains about a page’s worth of fighting detail. The Yellow Birds and Fobbit both depict scenes in which friendly and enemy soldiers and civilians kill and get killed, but the climatic “battle” scene in each is an incoming mortar or rocket round that takes the life of key character while unawares on the FOB. A true enough possibility, I well know, but not exactly a heroic way to go out. Or one that allows an author to portray combat at any length.

But Fobbit–contra to its title–actually does quite well depicting two episodes set outside the wire. In these, author David Abrams portrays dispute and potential violence between Americans and Iraqis that place American soldiers in the crucible of real-time, on-the ground decision-making, with many eyes watching, about whether to take a life or not. In the two scenes, a hapless officer underreacts in one tense stand-off involving a suicide bomber and overreacts in the other. In the first scenario, Abrams writes, “If someone had taken immediate action forty minutes ago, none of this would be an issue, but the commander on the scene–a pinch-faced captain named Shrinkle, known for his hems and haws–had waited too long.” A bold sergeant named Lumley takes charge, which needs to happen, but Abrams hints at the after-effects: “It would be a long time, years and years of therapy, before he could wipe from his mind the sight of that head erupting in a bloody geyser. He’d pulled the trigger without thinking through the consequences. He was not sorry he hadn’t hesitated but there was always that nagging, niggling doubt: maybe haji wasn’t going for the grenade….”

Abrams is on to something here; he seems to be saying that successful performance in combat isn’t so much a matter of bravery but of incisive decision-making under pressure. Here may be the gold waiting for extraction by future war novelists: not scenes of valor, but scenes of the mind as it decides what to do next, continuously, again and again, in difficult circumstances with important consequences.

Veterans Writing

Matt Gallagher’s latest post on the New York Times At War webpage explains the structural fault lines that divide the veterans writing community. Gallagher notes that veterans writing workshops are a growth industry, key components of the veterans programs now established in many colleges and cities. He notes that within the veteran writing community motivations differ. Some see writing as a matter of self-expression or healing. Others see it as a means by which they might turn themselves into big-time, well-regarded artists. Some think their stories need ultra-precise realistic rendering of their personal experiences and are unable to see the need for artistic re-imagining at all. Some veteran writers overvalue the degree to which their war experience makes them uniquely qualified to write about war. They scoff at the pretensions of someone who hasn’t “been there and done that” to write meaningfully and movingly about war.

These are all subjects that interest me. I’m familiar with veterans programs sponsored by colleges as diverse as Farmingdale State and Vassar, to say nothing of my occasional interaction with the veteran population at West Point. It occurs to me that the New GI Bill, which basically funds four years of college for anyone who has recently served overseas, is as worthy a program as the storied GI Bill of the post-World War II days, and that if we as a nation (or at least our government) are serious about our commitment to veterans, generous allotments for education are second only to effective medical care as a material, no-BS way of saying thanks. College is just the right place for many vets—they can simmer down after their service while preparing for their future–and it makes sense that classes that allow them to explore their war experience are part of the curriculum.

The question of whether a writer who hasn’t been to war can write well about war also intrigues me. Gallagher cites Ben Fountain as the example par excellence of an author who never served in the military, let alone saw combat, but who can still convey what it is like to be a soldier. I love Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk, too, but have noted that Fountain evades extended description of battle. Is that a place he just didn’t feel comfortable going? Brian Van Reet, a decorated vet, portrays two horribly mangled veterans in comic-grotesque terms in “Big Two-Hearted Hunting Creek.” Would a civilian feel as comfortable doing so? Is there something wrong with someone who isn’t disabled portraying characters who are? Both these cases reflect the issues of credibility and authority that permeate discussions of war writing.

We actually already have lots of fiction and non-fiction that describes what it is like to fight, and what it is like to live after fighting. Most of them are rendered largely through the perspective of one protagonist. I’m eager for a story that expresses the totality of an Iraq or Afghanistan deployment. A cast of characters, not just one main one. A vivid depiction of social milieu, from the squad up to the brigade, as they progress from home station to theater, spend a year on a FOB doing missions while interacting with local nationals, and then redeploy and get on with their post-war lives. A plot that takes a novel to properly set up and unfold. Where is that book? Fobbit, by David Abrams, comes close, but I want more. I’m now starting Sparta, by Roxana Robinson. Robinson’s not a vet, but maybe her book will take me there.

In the meantime, we might consider how a scene might be portrayed through poetry, through fiction, through personal experience. Here is how Brian Turner conveys his thoughts on the plane ride back from Iraq:

“Night in Blue”

At seven thousand feet and looking back, running lights

blacked out under the wings and America waiting,

a year of my life disappears at midnight,

the sky a deep viridian, the houselights below

small as match heads burned down to embers.

Has this year made me a better lover?

Will I understand something of hardship,

of loss, will a lover sense this

in my kiss or touch? What do I know

of redemption or sacrifice, what will I have

to say of the dead — that it was worth it,

that any of it made sense?

I have no words to speak of war.

I never dug the graves of Talafar.

I never held the mother crying in Ramadi.

I never lifted my friend’s body

when they carried him home.

I have only the shadows under the leaves

to take with me, the quiet of the desert,

the low fog of Balad,

orange groves with ice forming on the rinds of fruit.

I have a woman crying in my ear

late at night when the stars go dim,

moonlight and sand as a resonance

of the dust of bones, and nothing more.

And from early in Sparta, here is how Robinson depicts a similar scene:

The plane was full of sprawling, loose-lipped Marines, lost, gone, dead to the world.

Conrad liked seeing them like this: sleep was like salary, his men were owed. They were infantry grunts, and they’d been seven months on duty without a single day off. They deserved to sleep for months, years, decades. They deserved this long, roaring limbo, this deep absence from the world, from themselves. This plane ride was the floating bridge between where they’d been and where they were going—deployment and the rest of their lives. They deserved these hours of unconsciousness, this gorgeous black free fall.

My rendition of the same experience stems from a flight back from Afghanistan on mid-tour leave. I was the senior officer on a charter plane from Kuwait to Ireland. As such I sat up front and conversed with the senior flight attendant. She was maybe 30, with that half-pasty, half-refined look that comes from trying to maintain professional polish while living on hotel room service. She was very nice, and we traded stories while the rest of the plane dozed. Our flight was peaceful, and yet she told me of horrible flights out of Iraq in the bad days of 2006 and 2007, when soldiers would wake screaming out of nightmares born of bad memories and ravaged psyches. Seven hour flights would be filled with noise and bustle as fellow soldiers subdued distraught friends wacked out–or not wacked out enough–on Ambien. As we talked on she told me that she had gone to college at Indiana, as did I. That was cool, so I asked her where she hung out in Bloomington. To my surprise she mentioned the local punk rock club. Judging from her looks and job, I never would have guessed it, but she really knew her stuff. She had run a ‘zine, and still went to shows and knew all the bands. Since I had come-of-age near DC listening to classic hardcore groups such as Minor Threat and the Bad Brains, we had a lot to discuss. So, on through the flight we traded stories about our favorite records and shows. While 90% of the other passengers slept 90% of the time, my interlocutor lured me out of my deployment anxieties and uncertainty about the future with magical tales of a musical history that if we didn’t quite share, we both could appreciate.

My story isn’t as good as Turner’s or Robinson’s, or related as well, but it’s mine, which counts for something. All stories need telling, whether they find many listeners or not. It’s a social catharsis, enacted individually but resonating collectively.

New York Times review of Roxana Robinson’s Sparta

Veteran David Carrell writes about his return to college at Vassar

My War author Colby Buzzell writes about his own love of punk rock

The Aesthetics of Traumatic Injury

In October I will present at the American Literature Association War and Literature Conference on the portrayal of badly-wounded and disabled veterans in contemporary war literature. Two stories that prompted my thinking about the subject are Siobhan Fallon’s “The Last Stand” and Brian Van Reet’s “Big Two-Hearted Hunting Creek,” which I first wrote about in this blog here. I’m open to other suggestions, and I am reading lots of on-line veterans’ writing for more examples of the genre. The major war novels so far don’t seem to concern themselves so much with physical disability, though we might wonder about author Ben Fountain’s extended satirical skewering of Billy Lynn’s father in Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk. The demented, debilitated family patriarch, confined to a wheelchair after a stroke, doesn’t do much to enhance sympathetic understanding of the impaired, that’s for sure. Instead, his physical disability seems to symbolically manifest the lameness of his arch-conservative political views, the blindness of his hypocritical morals, and the impotence of his control over his family, his life, and the world.

Lameness, blindness, and impotence…. Disability activists would say those are good examples of how our language is infested with figures of speech that stigmatize the handicapped. Hmm….

So, the issue is vexed, both in life and literature, but that’s no reason not to explore it more fully, right? Below are three pictures taken from the popular domain of badly wounded and handicapped veterans. What are your thoughts as you view them? What do you think the photographers were trying to achieve? How are the photographs formally composed to be arresting? What are their ethics and politics? What about the “backstory” and post-publication history of each picture would you be interested in knowing and might help you understand them better?

War Photography: Ed Drew’s Wild Blue Yonder

Ed Drew is a US Air Force staff sergeant who is receiving publicity for his arresting photographs of fellow members of his helicopter squadron in Afghanistan. He speaks engagingly about his photos and views on art at this link, and he maintains a blog that features his photography before, during, and after his deployment as well as his poetry. Most remarkable about his Afghanistan photos is that they are “tintypes” or “wet plates”—a technique employed by Civil War photography pioneers such as Mathew Brady, but one that is far too cumbersome to be practical these days. Drew’s inspired decision to shoot using such archaic technology lends his subjects a timeless, stately, and elegiac feel. Because the photos depend on such long exposure and development times, they convey deep stillness and penetration, as if their subjects gave up more and more of their souls the longer the camera lingered. The choice of medium connects contemporary service with older traditions uncomplicated by problems associated with modernity, and suggest that soldiering is experienced and understood individually and in small units, shorn of global politics and large-scale social consequences.

Ed Drew is a US Air Force staff sergeant who is receiving publicity for his arresting photographs of fellow members of his helicopter squadron in Afghanistan. He speaks engagingly about his photos and views on art at this link, and he maintains a blog that features his photography before, during, and after his deployment as well as his poetry. Most remarkable about his Afghanistan photos is that they are “tintypes” or “wet plates”—a technique employed by Civil War photography pioneers such as Mathew Brady, but one that is far too cumbersome to be practical these days. Drew’s inspired decision to shoot using such archaic technology lends his subjects a timeless, stately, and elegiac feel. Because the photos depend on such long exposure and development times, they convey deep stillness and penetration, as if their subjects gave up more and more of their souls the longer the camera lingered. The choice of medium connects contemporary service with older traditions uncomplicated by problems associated with modernity, and suggest that soldiering is experienced and understood individually and in small units, shorn of global politics and large-scale social consequences.

Or, perhaps, the old-time-iness of Drew’s photos calls into question exactly those things—how dare we associate the high-tech, rigged-out warriors of the 21st-century with Brady’s bewhiskered 19th-century generals and battlefield dead—farmboys from north and south who fought the Civil War in bare feet?

I’m on surer ground when I allow Drew’s photos—which I love—to trigger a train of memories about my own interactions with Air Force personnel in Afghanistan, of which there were many. For example, I was and remain curious about the perspective of the airmen stationed at Manas Air Force Base in Kyrgyzstan, that purgatory through which soldiers and Marines passed on their way to and from Afghanistan hell. Even more I wonder about the small groups of airmen (some of whom were women) who made their way all the way downrage to the tiny FOBs on which I did my tour. All were great people, all were competent in their jobs, but the evidence that they had volunteered to serve their country specifically NOT by being placed in the way of direct fire weapons registered clearly on their faces upon arrival. Maybe not scared, but confused and dismayed at the proximity of so many Army infantry bubbas, men who daily rose to the challenge of rolling out the gate with a certain nonchalance or even swagger.

Not to be snarky, because Drew and his unit, an elite Combat Rescue team in Kandahar, saw plenty of action, but it is interesting that most of his photographic subjects are airmen decked out in soldierly kit and weaponry, with the hardened visages of experienced ground-pounding troops. In truth, “caveats” protected most Air Force personnel in Afghanistan; they served base jobs and were prohibited from missions deemed likely to see combat. But on the new-age circular battlefield, anything could happen anytime to anyone. I’ve written elsewhere about an Air Force medic, who while on a routine supply run, found himself in a battle patching up dozens of US, Afghan army, and Afghan civilian casualties. I also think of an Air Force captain who in response to a crisis was sent into sector as head of a squad of US Army soldiers to guard a lonely Afghan crossroads near the Pakistan border. Almost immediately, his squad was hit and suffered casualties. As night fell and bad weather set in, he found himself with wounded to care for, low water and ammunition, sketchy radio communication, and no hope of resupply, reinforcement, or evacuation until morning. Not the most dire situation ever, from an infantryman’s perspective, but probably more than the Air Force captain bargained for when he raised his right hand. For me, that sense of disorientation–an airman (and an artist at that) caught in a grunt’s war–helps explain Ed Drew’s curious eye and artistic hunger.

This post is dedicated to all the Air Force personnel with whom I served at Camp Clark and FOB Lightning, Afghanistan, 2008-2009.

Images copyright Ed Drew, courtesy of Robert Koch Gallery, San Francisco. Robert Koch Gallery website here.

War Poetry: W.H. Auden on the FOB

In an Atlantic magazine article, author Caleb Crain touts the virtues of memorizing poetry, and for him in particular the mid-20th century British poet W.H. Auden’s “In Praise of Limestone.” I’ve followed Crain for a while—he’s got a great blog—and I’ve also memorized many poems and prose passages. Not lately, though—trying to remember so much as a birthday these days brings me to my knees—but the ones I secured in my mind as a young man are still with me, friends for life. I like Auden, too, though I don’t know his work so well. But Crain’s essay recalls an anecdote from my tour in Afghanistan.

While stationed at FOB Lightning in Paktiya province, my hooch was in a “B-hut” partitioned into cubicles by plywood half-walls. Inside your space, no one could see you, but you could easily converse with your neighbor to either side. Next to me was a full-bird colonel whom I’d already come to know and respect. A veteran of three or four tours, he still threw on his body armor and clambered into an armored vehicle and drove out into sector 3-4-5 times a week. Just to put things in perspective, some hardcore infantry squads didn’t go outside the wire that much. The colonel was not just still brave and committed, but wise and practical and friendly and against lots of evidence to the contrary, optimistic and hopeful about Afghanistan.

When he heard that I had been a college English teacher, he asked me from the other side of our cubicle wall if I knew “September 1, 1939,” a poem Auden wrote about the beginning of World War II. I did, a little, or at least the first lines:

I sit in one of the dives

On Fifty-second Street

Uncertain and afraid

As the clever hopes expire

Of a low dishonest decade

My battle-hardened neighbor then told me that he knew the poem by heart and that he recited it to himself—all 99 lines of it–almost every day. He told me that he’d learned it in his first year at West Point, that it was the first poem he had ever loved and had always remained his favorite poem, and that it had inspired him to read much more poetry and to write verse himself. “From one thing, everything,” as the saying goes.

For the rest of the time that we were neighbors, the colonel would often recite the poem, or bits of it, to me. He would also probe me about my own knowledge or interest in Auden. I didn’t know much, but because I had access to that particularly modern accoutrement of contemporary deployment, a laptop computer with an Internet connection, I could cheat. I would bring up Auden on Wikipedia and feign expertise, unseen by my neighbor:

“So, did you know Auden visited the front lines of both the Spanish Civil War and the Sino-Japanese War?”

“Did you know that he actually hated ‘September 1, 1939,’” especially its most famous line, ‘We must love one another or die’?”

That was true. Auden had come to regard the sentiment as trite and the poem’s ending too smiley-faced:

Defenceless under the night

Our world in stupor lies;

Yet, dotted everywhere,

Ironic points of light

Flash out wherever the Just

Exchange their messages:

May I, composed like them

Of Eros and of dust,

Beleaguered by the same

Negation and despair,

Show an affirming flame.

Auden basically refused to speak about the poem and only rarely gave permission for it to be republished. But I love those lines, and so did the colonel, and so do many others.

I never discovered if the colonel realized that I was cribbing from the Internet, but I was trying to keep up with someone who knew a lot more about Auden than I did. Maybe he knew and didn’t care, or perhaps he enjoyed reversing the roles and being the teacher. He also knew a lot more about the US Army, working with Afghans, and fighting the Taliban than I did, and I learned plenty from him about those things, too.

Good man.

“Thank You for Your Service”: Ben Fountain’s Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk

Most vets know that queasy ambivalence that comes when a well-meaning American tells them, “Thank you for your service.” The sentiment is sincere, but also a little bit feeble, maybe even something of a back-handed compliment. Nowhere near as bad as, say, being spit upon, but being told “Thank you for your service” still registers flatly—the words are inadequate to or ignorant of what the service actually entailed, what the recipient might actually feel about the matter, or the responsibility and consequences that might actually come with bestowing thanks.

Most vets know that queasy ambivalence that comes when a well-meaning American tells them, “Thank you for your service.” The sentiment is sincere, but also a little bit feeble, maybe even something of a back-handed compliment. Nowhere near as bad as, say, being spit upon, but being told “Thank you for your service” still registers flatly—the words are inadequate to or ignorant of what the service actually entailed, what the recipient might actually feel about the matter, or the responsibility and consequences that might actually come with bestowing thanks.

That’s a lot of “actually” separating the words, the ideas, the deeds, and the people involved.

This conundrum gets writ large in Ben Fountain’s Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk. About an infantry squad being feted on a two-weeks-long “Victory Tour” for their heroism in Iraq, the novel culminates with “the Bravos’” participation in a garish halftime ceremony at a Dallas Cowboys football game. For the most part observing the dramatic unities of game-day, Texas Stadium time and place, BLLHW takes place on Thanksgiving, fittingly enough, and in a down-at-the-heels football Coliseum Fountain describes as looking like “a half-assed backyard job” and suggestive of “soft paunches and mushy prostates.” The novel is focalized through the eyes of Billy Lynn, the most heroic of the Bravos and the one most sensitive to the Texas-sized admixture of adulation and condescension the squad encounters. The mostly white, mostly rich, mostly male, and very gregarious Cowboy fans are eager to honor real-live war heroes, but they don’t really know how to behave in the presence of actual—that word again–ragamuffin grunts. The soldiers’ valor in combat obviously gives lie to their own pretensions of manliness, and slights, misunderstandings, and awkwardness accumulate throughout the course of the novel. After outright hostility and confrontation ensue, the Bravos are hastened back (and hasten back) to war, and the tiny fissures of attitude and values that divide the serving soldiers and the homefront populace have widened into a Texas-sized chasm of mutual incomprehension and incompatibility.

Fountain never served in the military, but neatly sidesteps issues of authenticity and authority by minimizing the amount of page-space given to the Bravos’ time overseas and in combat. The battle scenes that made them famous are described as they were captured by the news film crew that recorded their exploits and as they now exist in the swirl and haze of Billy’s memory. Fountain is on much surer ground describing events at home, where his impressive powers of observation, imagination, representation, and speculation get right not only the rough-love camaraderie of the Bravos, but skewer again and again the comfy and sheltered pretensions of an upper-class America too distracted by material, commercial, and celebrity excess to think well, or really even care deeply, about the nation’s wars. Fountain writes in the hopped-up razzmatazz style of Tom Wolfe, with lots of over-the-top figures of speech and nonstandard ways of arranging text on the printed page to represent speech and sound. Crazed metaphors and similes appear by the dozens, such as the following one oft-quoted in reviews and too good to pass up here. In a flashback scene, Fountain describes Billy lying in the sun with his smoking-hot bikini-clad sister and noticing her crucifix, a “small gold cross [that] lay on the swell of her breasts, a tiny mountaineer going for the top.”

Indeed, though an issue here is one of the book at large: Billy is far too inarticulate in speech and inchoate in thought to be the vessel for the piercing social critique and linguistic pyrotechnics Fountain favors. Billy can barely remember what happened in combat, is confused by the notion that he is a hero, dreads going back to war, is helpless in the face of calamities that have overtaken his family, is unhappy at the game, and is preoccupied by his virginity, which he very much wants to shed. Getting laid is the only token of gratitude from a grateful nation that Billy really wants, and his failure to entice even one member of America’s collective womanhood to indulge him—on his own Victory Tour, for crying out loud—exacerbates his self-loathing and plunges him into periodic funks. “Billy, you’re flaking out on me again,” his squad leader cautions him repeatedly. Billy seems to be the kind of guy who always knows a little more or a little less than everyone else, but Fountain describes him as also possessing a sweet charisma that is respected by savvier male characters and which actually—that word once more–makes him adorable to women. Along with everything else, BLLHW is a love story, and though Billy doesn’t (quite) lose his virginity before heading back to Iraq, he connects, at least for a moment, physically and emotionally with an equally sweet and endearing Dallas Cowboy cheerleader. This plot line strains credulity, but is enjoyable nonetheless. A fleeting romance among the ruins seems to be the least Billy, for whom the reader has come to feel strongly, deserves–our tiny mountaineer makes it for a moment to the top.

An audio clip of Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk is available here.

Ben Fountain’s Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk: A Novel. HarperCollins (2012)

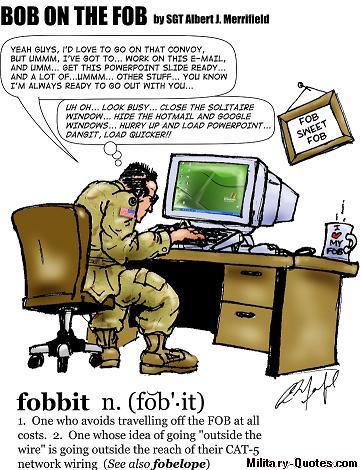

In the Rear with the Gear: David Abrams’ Fobbit

Often compared in reviews to Catch-22 and M*A*S*H, David Abrams’ Fobbit portrays the Forward Operating Base, or FOB, as the material manifestation of the conceptual perversity and corruptness of the US military mission in Iraq (and by extension Afghanistan). Fobbit’s exposé of rear-echelon life and culture supports the sneaking suspicion of many deployed soldiers that victory was doomed as long as the FOB, with all its bloat and isolation, served as the locus from which the fighting forces might generate the will, the might, the ingenuity, and the resources necessary to defeat the wily foe on the other side of the base barrier walls. We’re lucky that Abrams, a writer with a laser-like eye for character, social context, and telling detail, has chosen black humor as his mode of expression. Though the novel ends horribly for its characters (as does Catch-22), most of it is played for laughs. I’ll speculate that Abrams has taken it easy on the Army out of an affection borne of 20 years of service as an award-winning Army journalist. Were the tone serious, the bloodletting would be merciless and unbearable.

Often compared in reviews to Catch-22 and M*A*S*H, David Abrams’ Fobbit portrays the Forward Operating Base, or FOB, as the material manifestation of the conceptual perversity and corruptness of the US military mission in Iraq (and by extension Afghanistan). Fobbit’s exposé of rear-echelon life and culture supports the sneaking suspicion of many deployed soldiers that victory was doomed as long as the FOB, with all its bloat and isolation, served as the locus from which the fighting forces might generate the will, the might, the ingenuity, and the resources necessary to defeat the wily foe on the other side of the base barrier walls. We’re lucky that Abrams, a writer with a laser-like eye for character, social context, and telling detail, has chosen black humor as his mode of expression. Though the novel ends horribly for its characters (as does Catch-22), most of it is played for laughs. I’ll speculate that Abrams has taken it easy on the Army out of an affection borne of 20 years of service as an award-winning Army journalist. Were the tone serious, the bloodletting would be merciless and unbearable.

Joseph Heller supposedly said that to write Catch-22 “all he had to do was take notes” while serving in the World War II Army Air Force. Abrams obviously kept his pen-and-pad nearby, too, while the Army around him unveiled the laughable reality behind the pretence of organization, efficiency, and idealism. Fobbit’s plot tracks the parallel lives of a variety of soldier types easily recognizable by veterans: the Army captain hopelessly over his head as a leader of warriors, other much more decisive officers and NCOs who just seem at home in combat, and a variety of rear-echelon staff officers, sergeants, and troops (the “fobbits” of the novel’s title) preoccupied with rationalizing their feeble contributions to the war effort. Many of these types get their say, but most of the novel is focalized through the perspective of Staff Sergeant Chance Gooding, Jr., a Public Affairs non-commissioned officer whose job and views seem to reflect Abrams’ own. The coin of the social capital realm on Gooding’s FOB is competence and courage in action—an even question the novel proposes is whether it is worse to fight and find oneself lacking or to never have fought at all. Fobbit’s answer is that the two are equally bad: from a fobbit’s point-of-view, a war that doesn’t allow all its participants to excel in battle is mean and unfair, besides being deadly and horrible.

Big picture considerations aside, Abrams doesn’t miss many of the foibles of FOB life and its minor characters: the smoke shack heroes whose braggadocio matches their nicotine consumption while standing in inverse proportion to the time they’ve spent outside the wire; the hot chick who is not going to sleep with everyone, but might do so with at least somebody; the hard infantrymen who give the lie to the soft comfort of the fobbits and make them ashamed of themselves. “They also serve who stand and wait,” wrote John Milton, but if all your standing and waiting is in line at the Dining Facility, it’s tough to feel especially good about your deployment. Or how your nation has organized itself to fight the war. In my experience, though, many fobbits seemed to enjoy their year overseas. Squeaky clean from daily showers and weekly laundry, plump from three hot meals a day, padding from bunk to workplace to chow hall to PX to gym to MWR center, oversized M16s slung awkwardly across their backs, mindful of the virtual military requirement to be perpetually chin-up and cheerful, lots and lots of fobbits appeared to be having a good time. Honestly, they just seemed high on the shared experience of danger, distance from home, and life shorn of decisions and distractions.

Of course there were exceptions, such as the male soldier whose marriage was floundering, or the single-mom female soldier whose child care plan had fallen apart. And Abrams-slash-Gooding’s perch inside a division “G1 Personnel” Public Affairs Office rendered him full access to the most misery-producing structure of life on a FOB: duty on a battalion, brigade, division, corps, or task force headquarters staff. Having experienced it myself, it’s hard to imagine jobs better designed to enrage and enfeeble a middle-aged officer, nominally at the height of his or her adult powers, but now reduced to bone-grinding servitude and routine, interspersed by always terrifying and usually humiliating interactions with full-bird colonels and general officers. As a career non-com, Abrams must have often wondered at the unholy conglomerations of bureaucratic rigmarole in which he was snared, concocted by superior officers and said to be responsible for the operational, logistical, and administrative support of the fighting force. That these self-constructed torture chambers made their inhabitants deeply unhappy must have seemed clear. That they were necessary for the effective conduct of the war much less so.

An excerpt from Fobbit, from David Abrams’ webpage.

David Abrams’ Fobbit: A Novel. Grove Press-Black Cat (2012).