Significant stagings of plays about Iraq and Afghanistan are accumulating. The Great Game, a compendium of 12 short plays exploring Afghanistan history from antiquity to the current period, opened in London in 2009, went on tour in America in 2010, and has continued to be performed in various venues since. Robin Williams starred in 2011’s Bengal Tiger at the Baghdad Zoo, a play set in the post-invasion Iraq of 2003. Blood and Gifts, about Cold War battles for influence in Afghanistan in the 1980s, ran at the Lincoln Center in New York City over the 2011-2012 winter season.

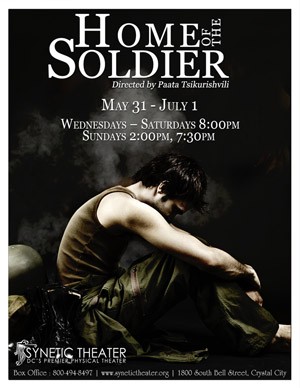

Last summer, I had a chance to see a less known but still interesting production called Home of the Soldier. Written by Ben Cunis and staged by the Synetic Theater, an experimental troupe based in Arlington, VA, Home of the Soldier portrays US soldiers in training and on deployment to an unspecified foreign country. Iraq and Afghanistan are never mentioned, but the hyper-edgy staging make it pretty clear that the play has our contemporary wars in mind. On deployment, the soldiers’ camaraderie and ethics are challenged by the complexities of modern war. The play was wonderful to watch. Light, sound, and set were terrific. The young, lithe actors were charismatic as hell. A scene that portrays an IED explosion actually rung true in a way that I wasn’t prepared for at all. In most ways, then, Home of the Soldier was up to the challenge of portraying war, even in a highly stylized way featuring electronic music, athletic dance, and multi-media visual effects.

The plot, however, was a little loopy. Besides depicting the loss of innocence of its protagonists—a war story cliché–it involved a weird and implausible amalgam of father-son Oedipal dynamics and a Hurt Locker-style individual venture outside the wire to help innocent noncombatants. I take its interest in showing US soldiers in more personal contact with local nationals than military missions typically allow to be a theme that writers and artists are attracted to. Perhaps they feel it is THE story that needs to be told, or perhaps the story with the most dramatic potential.

I don’t think these things are true, though, in part because the shape of deployment makes them unfathomable. Soldiers experience war most intensely in human terms on FOBs in their relations with other soldiers; outside the wire they operate as teams and units and their interactions with local civilians are highly impersonal, business-like, and fleeting. Home of the Soldier’s effort to personalize an engagement with individual foreign citizens might represent a critique of how we actually have waged our wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, but it doesn’t jibe with how most of the 100s of thousands of soldiers who have deployed have actually experienced them.

So, if no story yet that I know of has portrayed or even could portray a realistic relationship with an Iraq or Afghanistan citizen over the course of a soldier’s deployment, what are some other possibilities? Well, no writer yet has told the story of a unit embarked on a mission to accomplish something interesting or important. No one yet has explored the nuances of squad dynamics or brought an intense leader-led relationship into the highest relief. No one yet has told the story of a unit over the period of its deployment, with all the individual and group tales that would mark its deployed life. Even the memoir and historical record of these things is scant.

The general problem is that of creating a plausible and compelling storyline to animate a fictional representation of deployment “in theater” (meaning not in the playhouse, but the Iraq/Afghanistan area of operations). Literature, drama, and film so far have centered on exploration of psychology and emotional affect and political implication. These stories and artworks do well with scene, vignette, incident, mood, and idea, but their narrative drive has been feeble. They struggle at the level of time and duration and suspense–the representation of emotional lives and interpersonal relationships under pressure to change.

One way to illustrate this is to examine, quickly, how writers have sought to portray soldiers’ romantic relationships. There’s got to be a girl or guy, right, but what’s the story to tell? The romantic life of real deployed soldiers is mediated through electronic technology such as Skype, email, social media, and chat. It might also take the shape of crushes on or even illicit affairs with fellow soldiers. Each of these options is a stunted, malnourished approximation of a real relationship, hard to be traced with the richness of experience and impression that characterizes and energizes narrative. A quick synopsis of the romantic subplots of some war fiction reveals the extent to which authors must contort their stories to capture the narrative power of romance:

Siobhan Fallon has written one story, “Camp Liberty,” about a soldier who develops feelings for a female interpreter. It’s a great story and actually not an impossible scenario at all. In “Inside the Break,” a wife back home puts the kabosh on her soldier-husband’s fling with another soldier on his FOB. But other than those two stories, Fallon trains her eye on the relationship of soldiers and spouses after deployment.

Ben Fountain, in Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk, has his hero, back in the States, fall for a Dallas Cowboy cheerleader who, amazingly enough, reciprocates his attention. Totally crazy, but also totally awesome how well Fountain pulls it off.

Kevin Powers’ The Yellow Birds portrays an unconsummated relationship of a male soldier with a female soldier. Also very plausible, but in The Yellow Birds the relationship is so faint as to be more a fantasy than an actuality.

I haven’t read David Abrams’ Fobbit, but if it’s as good and funny as everyone says it is, it will hold up the romantic and erotic circuitry of FOB-life for satirical description and evaluation. I’m looking forward to finding out. In the meantime, this Washington Post opinion piece by a woman vet about sex in a war zone hints at some possibilities:

Washington Post Home of the Soldier review

New York Times The Great Game review

New York Times Bengal Tiger at the Baghdad Zoo review