Below I’ve catalogued memoirs, imaginative literature, and big-budget films published or released through the end of 2014 that represent important and interesting takes on America’s twenty-first century wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. The lists are subjective and idiosyncratic, not complete or authoritative. Still, they might help all interested in the subject to more clearly and widely view the fields of contemporary war literature and film. I’ve arranged the lists chronologically and within each year alphabetically by author or director. If I’ve misspelled a name or title, gotten a date wrong, or omitted a work you think important, please let me know and we’ll make the list better.

If the author or director has served in the US military, or is the spouse of a veteran, I have annotated the branch of service in parentheses.

The lists of “Important Precursor” texts and films represent works that I think are well known and influential among today’s war artists. A list of stage, dance, and performance war art is forthcoming.

Important Precursor Texts:

Michael Herr: Dispatches (1978)

Tim O’Brien (Army): The Things They Carried (1990)

Yusef Komunyakaa (Army): Neon Vernacular (1993)

Anthony Swofford (USMC): Jarhead (2003)

Important Precursor Films:

Oliver Stone (Army), director: Platoon (1986)

Stanley Kubrick, director: Full Metal Jacket (1987)

Ridley Scott, director: Blackhawk Down (2001)

Contemporary Fiction:

Siobhan Fallon (Army spouse): You Know When the Men Are Gone (2011)

Helen Benedict: Sand Queen (2011)

David Abrams (Army): Fobbit (2012)

Ben Fountain: Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk (2012)

Kevin Powers (Army): The Yellow Birds (2012)

Joydeep Roy-Bhattacharya: The Watch (2012)

Nadeem Aslam: The Blind Man’s Garden (2013)

Lea Carpenter: Eleven Days (2013)

Masha Hamilton: What Changes Everything (2013)

Hilary Plum: They Dragged Them Through the Streets (2013)

Roxana Robinson: Sparta (2013)

J.K. Rowling (aka Robert Galbraith): The Cuckoo’s Calling (2013)

Katey Shultz: Flashes of War (2013)

Fire and Forget: Short Stories from the Long War, edited by Roy Scranton (Army) and Matt Gallagher (Army) (2013)

Greg Baxter: The Apartment (2014)

Hassan Blasim, The Corpse Exhibition (2014)

Aaron Gwyn: Wynne’s War (2014)

Kara Hoffman: Be Safe, I Love You (2014)

Atticus Lish (USMC): Preparation for the Next Life (2014)

Phil Klay (USMC): Redeployment (2014)

Michael Pitre (USMC): Fives and Twenty-Fives (2014)

Contemporary Poetry:

Juliana Spahr: This Connection of Everyone with Lungs (2005)

Brian Turner (Army): Here, Bullet (2005)

Walt Piatt (Army), Paktika (2006)

Jehanne Dubrow (Navy spouse): Stateside (2010)

Elyse Fenton (Army spouse): Clamor (2010)

Brian Turner (Army): Phantom Noise (2010)

Paul Wasserman (USAF): Say Again All (2012)

Colin Halloran (Army): Shortly Thereafter (2012)

Amalie Flynn (Navy spouse): Wife and War (2013)

Kevin Powers (Army): Letter Composed During a Lull in the Fighting (2014)

Contemporary Memoir, Blog-writing, and Reportage:

Colby Buzzell (Army): My War: Killing Time in Iraq (2005)

Kayla Williams (Army): Love My Rifle More Than I Love You: Young & Female in the U.S. Army (2006)

Nathaniel Fink (USMC): One Bullet Away (2006)

Marcus Luttrell (Navy) and Patrick Robinson: Lone Survivor (2007)

Peter Monsoor (Army): A Brigade Commander’s War in Iraq (2008)

Craig Mullaney (Army): The Unforgiving Minute (2009)

Matt Gallagher (Army): Kaboom: Embracing the Suck in a Savage Little War (2010)

Benjamin Tupper (Army): Greetings from Afghanistan: Send More Ammo (2011)

James Wilhite (Army): We Answered the Call: Building the Crown Jewel of Afghanistan (2010)

Benjamin Busch (USMC): Dust to Dust (2012)

Brian Castner (Air Force): The Long Walk: A Story of War and the Life that Follows (2012)

Sean Parnell (Army): Outlaw Platoon (2012)

Ron Capps (Army): Seriously Not All Right: Five Wars in Ten Years (2013)

Stanley McChrystal (Army): My Share of the Task (2013)

Adrian Bonenburger (Army): Afghan Post: One Soldier’s Correspondence from America’s Forgotten War (2014)

Jennifer Percy: Demon Camp (2014)

Brian Turner (Army): My Life as a Foreign Country (2014)

Photography:

Sebastian Junger: War (2010) and Tim Hetherington and Infidel (2010)

Benjamin Busch (USMC): The Art in War (2010)

Michael Kamber: Photojournalists on War: The Untold Stories from Iraq (2013)

Film:

Kathryn Bigelow, director: The Hurt Locker (2008)

Sebastian Junger, director: Restrepo (2009)

Oren Moverman, director: The Messenger (2009)

Kathryn Bigelow, director: Zero-Dark-Thirty (2012)

Peter Berg, director: Lone Survivor (2013)

Sebastian Junger, director: Korengal (2014)

Claudia Myers, director: Fort Bliss (2014)

Criticism:

Elizabeth Samet: Soldier’s Heart: Reading Literature Through Peace and War at West Point (2007)

Stacey Peebles: Welcome to the Suck: Narrating the American Soldier’s Experience in Iraq (2011)

Elizabeth Samet: No Man’s Land: Preparing for War and Peace in Post-9/11 America (2014)

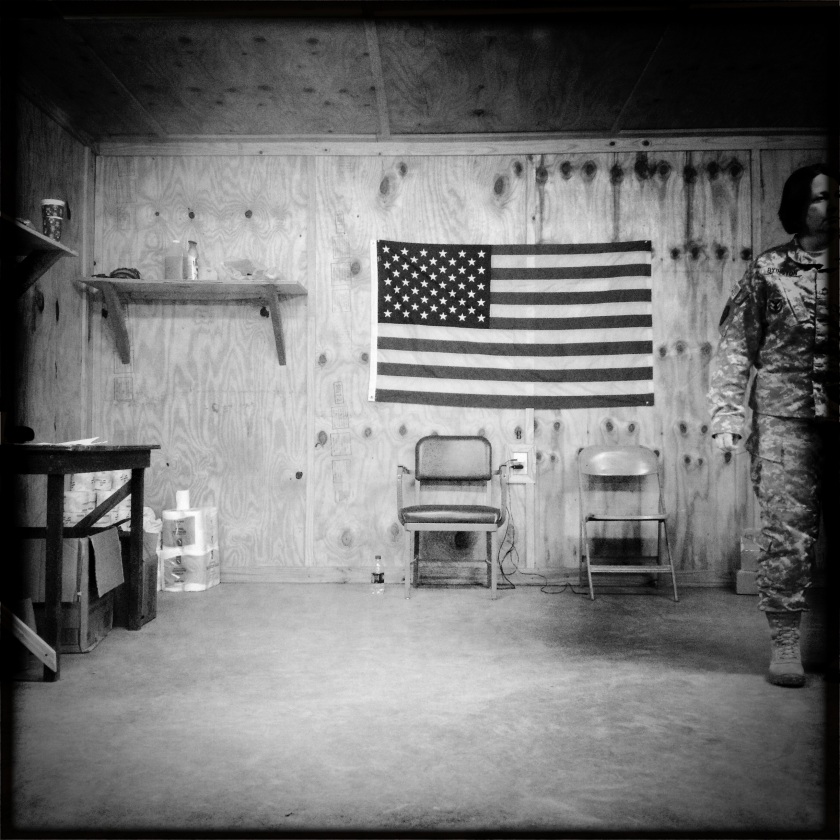

A caveat up-front is that my lists do not reflect hundreds of stories, poems, and photographs published individually in anthologies, magazines, and on the web. Some of my favorite stories, by authors such as Mariette Kalinowski, Maurice Decaul, Will Mackin, and Brian Van Reet, and photographs, such as the one by Bill Putnam published here, thus do not appear above, though I hope to post more comprehensive lists in the future.

Another deficiency is the lack of works by international authors and filmmakers, particularly Iraqi and Afghan artists. Again, that project awaits completion.

My list of memoirs is probably the most subjective. The works I’ve listed are those I think important historically or interesting to me personally, with a small nod toward providing a variety of perspectives. The small number of photography texts I’ve listed combine evocative pictures taken at war and on the homefront with insightful commentary written by the photographers and collaborators themselves.