I was asked to compile a list of twentieth and twenty-first century novels and short-story collections about war authored by American veterans. I was limited to ten titles—two for each of our major conflicts—but I broke the rules and chose three each for World War II and the Global War on Terror. Here’s my list:

World War I

John Dos Passos (US Army Medical Corps), Three Soldiers (1919)

Ernest Hemingway (American Red Cross), A Farewell to Arms (1929)

I know Hemingway wasn’t technically in the military, and Dos Passos only served for a short time, but it’s too hard to ignore the connection between their war-time exploits and the books they authored about the war. I was tempted to include F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby because I’ve always been intrigued by the reference to Gatsby’s service in a “machine gun battalion” in The Great War, and I know Fitzgerald wrote This Side of Paradise while in uniform at Fort Leavenworth. But neither of those reasons are fulsome enough to include either work. I also wish two other WWI veterans who turned out to be estimable writers, E.E. Cummings and Malcolm Cowley, had written fiction based on the war, but it was not to be.

World War II

Joseph Heller (Army Air Corps), Catch-22 (1961)

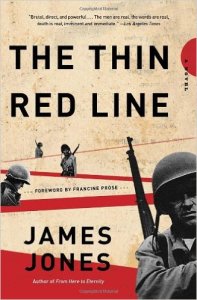

James Jones (Army), The Thin Red Line (1962)

Kurt Vonnegut (Army), Slaughterhouse Five (1969)

All three works are marvels. Catch-22 and Slaughterhouse Five I read when young and they helped me understand how war might best be described using humor, satire, and irony. The Thin Red Line I read recently and was stunned by how interesting and perceptive it was.

Korea

James Salter (Air Force), The Hunters (1956)

Richard Hooker (H. Richard Hornberger) (Army), MASH: A Novel About Three Army Doctors (1969)

Salter’s novel about Air Force fighter pilots is great; any writer who can write sentences as finely tuned as the following has my respect:

“Flying with him was like being responsible for a child in a crowd.”

“He was not fully at ease. It was still like being a guest at a family reunion, with all the unfamiliar references.”

“It was still adventure, as exciting as love, as terrible as fear.”

“The sky seemed calm but hostile, like an empty stadium.”

MASH: A Novel About Three Army Doctors affects the insouciant air toward military authority and bureaucracy that the popular TV show it inspired excelled at. Honestly, though, MASH-the-novel seems a little thin and, in some aspects, such as its racial humor, dated.

Vietnam

Larry Heinemann (Army), Paco’s Story (1986)

Tim O’Brien (Army), The Things They Carried (1990)

Rereading these two highly-regarded works made me realize how entrenched in their time they are: They privilege the experience and views of the combat grunt and the angry veteran to the point of mythologizing them and they’re obsessed with authority, credibility, authenticity, and right-to-speak issues. Vietnam War fiction badly needs historicizing to measure its preoccupations and how much it really has to say to to contemporary war fiction.

Iraq and Afghanistan

David Abrams (Army), Fobbit (2012)

Kevin Powers (Army), The Yellow Birds (2012)

Phil Klay (Marines), Redeployment (2014)

Cutting things off somewhat arbitrarily at 2014, I’m limiting the contemporary war listings to two National Book Award nominees (The Yellow Birds and Redeployment, with Klay’s short-story collection taking the prize) and one (Fobbit) that might well have been. All of them pay homage to the tradition of veteran-authored war fiction while working changes upon it, commensurate with the changing times and their authors’ unique perspectives.

So that’s my veteran-author war fiction canon for your consideration and debate. It’s a great tradition, all-in-all, and I enjoyed reading or rereading these books and many others over the summer and making my choices. The books that impressed me most were James Salter’s The Hunters and James Jones’ The Thin Red Line. Saving The Hunters for another day, I say a little more about The Thin Red Line below. Considering Jones’ achievement made me wonder why no contemporary veteran-author has yet written a novel about the year-long deployment to Iraq or Afghanistan of a platoon, company, or battalion with the same anthropological overview as Jones. It would seem like a natural. Most soldiers experienced the wars as cogs in complex social organizations artificially and temporarily arranged to both protect them and prepare them to give up their lives. Arguably what was going on around them and outside of them was of more interest and importance—and definitely more various—than what was happening to them and inside of them individually.

****

What People Mean When They Talk About “Panoramic” War Novels: James Jones’ The Thin Red Line

The literary artistry of James Jones’ novel The Thin Red Line is hard to define and in some ways hard even to detect. On one level, his account of a US Army infantry company’s exploits from their arrival on Guadalcanal during World War II to their departure proceeds at the level of realistic description that resembles journalism and history. Even when we factor in his attention to the human stories of the members of “C-for-Charlie” Company—their fears, desires, backstories, and emotions—it still seems, in many respects, to aspire to a common sort of long-form non-fiction narrative that embraces both big events and individual profiles.

The literary artistry of James Jones’ novel The Thin Red Line is hard to define and in some ways hard even to detect. On one level, his account of a US Army infantry company’s exploits from their arrival on Guadalcanal during World War II to their departure proceeds at the level of realistic description that resembles journalism and history. Even when we factor in his attention to the human stories of the members of “C-for-Charlie” Company—their fears, desires, backstories, and emotions—it still seems, in many respects, to aspire to a common sort of long-form non-fiction narrative that embraces both big events and individual profiles.

The particular and peculiar way that Jones manipulates the register between exterior actions and interior views is what is so hard to pin down. That The Thin Red Line is panoramic in a way no contemporary war novel is a testament as much to Jones’ imagination as it is to the fact that he must have taken good notes while he was in the Army. Jones provides extensive accounts of the actions and thoughts of roughly fifteen members of C-for-Charlie, from privates through the four company commanders who lead them on Guadalcanal, and maybe thirty other enlisted soldiers and officers appear as minor characters. He describes the men as they prepare to disembark from their troop transport ship, in their early days on the island as they acclimatize to the jungle climate and prepare to go into battle, a week’s worth of harrowing combat on a hill mass known as The Dancing Elephant, a couple of weeks recouping in a rest area, and then another week of combat to seize a hill named The Giant Boiled Shrimp and a village named Boola Boola, followed by a brief period of recovery before they depart Guadalcanal enroute to another South Pacific island.

Jones, who fought on Guadalcanal, tells us in a forward that the physical geography and battles he describes are imaginary, but surely he wants to relate in as much detail as possible what infantry combat looks like tactically and feels like emotionally, seemingly in a corrective to other authors’ accounts of battle. Tactically, he precisely and compellingly explains how platoons, companies, and battalions go into battle and how the land on which they fight—the hills, dales, dips, furrows, outcroppings, and other geographical features, plus the vegetation—impact the fighting at every turn, both for the bigger units and the individual soldier. He is very interested in what happens when a unit comes under fire, takes casualties, and then collects itself to seize objectives and complete missions. His account of how the dread felt by infantrymen before battle intensifies in combat and threatens to paralyze them until they become hardened to the prospect of their death is especially astute. He is very interested in the fact that some men perform well in combat and others don’t; while some of C-for-Charlie’s heroes are predictably wily, feisty types whom you might think would do well in a fight, not all are, and the distribution of fear and courage is anything but systematic: men brave in one instance, freeze up in another, while some men who know themselves to be cowards find ways to perform well under fire, at least sometimes. Jones is also interested in leadership, how NCOs and officers through some peculiar amalgamation of judgment, decisiveness, words, actions, luck, and circumstance cement their ability to lead troops in combat in the eyes of their superiors, their men, and in their own minds. Three successive commanders of C-for-Charlie, for example, are relieved-for-cause, and it doesn’t always seem fair, but rather than rendering judgment, Jones traces the contours by which faith in their ability ebbs away. Among the enlisted soldiers, a steady rate of attrition opens up opportunities for the most ambitious and combat-capable of underlings to rise to the top in a process that would be almost Darwinian were it not for the fact that death and injury in battle often strike without regard for who’s fittest.

Considered as a social organism, C-for-Charlie in Jones’ portrait seems organized not so much by rank, but by a ruthless jockeying for regard by its members, which is usually framed in terms of manhood—who is toughest, who is most aggressive, who is most cocksure, who is most competitive, who wants whatever he wants the most. In this milieu, men are quick to judge each other as punks, lightweights, and cowards, and are driven by furious impulses toward revenge, jealousy, and entitlement, engendered by sleights and perceived grievances big and small. The camaraderie of men bound by a sense of family is documented, but selfishness and contempt more than love and care define the soldierly bond. The C-for-Charlie family is perverse in other ways, too, most notably by the flux of its membership engendered by death, evacuation for wounds, or reassignment, as in the case of its commanders. Characters are whisked out of the book on nearly every page, rarely to be heard from again, an effect that is as unsettling for readers as it must have been for the unit, and each removal generates a seismic recalibration not just of the official rank structure, but of the homosocial lineaments of C-for-Charlie culture.

Jones’ attitude toward his soldier-characters is part of The Thin Red Line’s curious allure. The odd use of “C-for-Charlie”—a way of referring to an infantry unit I’ve never seen before (yes, I know there are C Companies, often called Charlie Company, in infantry battalions, but consistent use of “C-for-Charlie” is idiosyncratic)—has the effect of anthropomorphizing a military organization, but Jones doesn’t privilege the point-of-view or experiences of any of its individual members. The company first sergeant, a philosophical type with a drinking problem, appears in the novel’s opening and closing scenes, but seems to have changed little from beginning to end and doesn’t loom especially large in the events that befall C-for-Charlie. A second character, a company clerk named Fife, a coward at heart who finds himself at least temporarily capable of battlefield prowess, occupies the most page space in the novel. But he too is whisked off the page short of the conclusion, and The Thin Red Line can hardly be said to be his story.

Jones seems interested in every aspect of C-for-Charlie’s existence on Guadalcanal, so scenes in the rear area receive almost as much attention as scenes of battle, and he also seems very interested in telling a war story without resorting to sentimentalism and sensationalism. Nor does he seem to be telling an “anti-war” story, though its clear enough after reading The Thin Red Line that war is a horrible human endeavor, and the military is a horrible way of organizing people socially. Though dramatic things happen—many of them—drama is never milked for effect—that some soldiers might butt-fuck each other the night before battle is related in the same register as scenes of horrific wounding or tremendous acts of bravery or a drunken brawl in a rest area after battle. And yet the forward pace of the novel proceeds inexorably; Jones’ artistry finds the right word-web to mirror how the propulsive forces of military culture and war shape the little lives of its participants, yet where the military and war disdain human life, Jones manages the tricky feat of inculcating interest in his characters without saturating them and his readers in a goo of sympathetic identification. The soldiers’ lives play out or end on Guadalcanal somewhat as if subject to fate as hypothesized by Shakespeare’s Gloucester, “As flies to wanton boys are we to Gods, they kill us for their sport,” but that implies that men’s lives, precious to the men themselves, are at least of sadistic interest to higher powers. In The Thin Red Line’s cosmos, men live and die more as if subject to James Joyce’s vision of God, one who pares his nails indifferently while looking down on his creations. To search for other analogies in literature, the men of C-for-Charlie seem like the battling ants described by Thoreau in Walden, viewed from on high with forensic interest, but in Jones now endowed with thoughts and personalities. The Thin Red Line not only is not character-driven, it’s not plot-driven, either, and yet still—again, Jones’ artistry at work—it is not just a “one thing after another” chronological narrative. The sense that a novel creates a social microcosm that replicates the cosmic working out of character and event of real life is a tenet of the realist and naturalist novel, which are outdated genres, but The Thin Red Line feels anything but dated—if anything it is a bracing reminder of what supremely talented authors are capable of. It’s hard not to think that no one writes novels like The Thin Red Line anymore because Jones has done it as well as it can be done, but still, I’d like to see contemporary authors try.

Finally, all my praise above would just be moot if it were not for Jones’ greatest gift: his ability to consistently write amazing sentences, to say things in ways that just startled me with their unanticipated aptness. I can’t remember a book that I found myself turning down more page corners to remind myself of passages to which I wanted to return. I could list quite a few, but in the name of even-handedness, there are a few clinkers, too. In the library copy I read, a previous reader circled the words “more good” where Jones might have used “better” and placed a question mark in the margin. Toward the end of the novel, a lieutenant loses part of his hand when a grenade he is throwing explodes prematurely. Jones attributes it to the neglect of the distracted, careless woman who cut the fuse too short in the ordnance factory where it was assembled; the aside seems contrived and crude. Finally, I didn’t like the book’s epigram, in which Jones thanks “war” for providing so much material of interest. The tone is satirical and manic and not a good prelude at all for the cool and laconic prose voice of the novel’s narrative. But those are minor exceptions in a 500-page book that otherwise impresses on every page.

Many thanks to Roy Scranton, Rachel Kambury, and Drew Pham–fellow members of an informal TTRL admiration society.

What a terrific post! Sometimes these top-war-lit lists get so long that it’s refreshing to “thin the herd” a little and hear about someone’s favorites. It’s also nice to see a list that leans towards literary merit.

I, too, have always thought of GATSBY as a WWI novel as much as a “jazz age” novel. I am so glad to see the darkly cathartic FOBBIT on the list (not surprised, of course). And this makes me very much want to read THE THIN RED LINE!

I just started Sigfried Sassoon’s 2nd novel in the George Sherston trilogy for some research. Just curious – what kept Sassoon off your WWI list?

Thanks, Andria, no Sassoon because I was limited to fiction written by American vets. I haven’t read Sassoon’s novels, but I read recently Pat Barker’s Regeneration, about Sassoon, if that counts. I didn’t even know Sassoon wrote novels, but checking Wikipedia I learn he wrote “fictionalized autobiography” under an assumed name. That’s weird enough to get my attention. Re TTRL, life is short and the novel’s long, so your call–hopefully I haven’t over-hyped it.

Oh, right! American authors! I guess that makes the list a *little* more manageable!

It was actually hard to find all those titles, plus a few that didn’t make the cut–many Inter-Library Loans required.

Hmmm, Peter, you write:

“Considering Jones’ achievement made me wonder why no contemporary veteran-author has yet written a novel about the year-long deployment to Iraq or Afghanistan of a platoon, company, or battalion with the same anthropological overview as Jones. It would seem like a natural.”

And:

“That The Thin Red Line is panoramic in a way no contemporary war novel is. . . . ”

As well as:

“The sense that a novel creates a social microcosm that replicates the cosmic working out of character and event of real life is a tenet of the realist and naturalist novel, which are outdated genres, but The Thin Red Line feels anything but dated—if anything it is a bracing reminder of what supremely talented authors are capable of. It’s hard not to think that no one writes novels like The Thin Red Line anymore because Jones has done it as well as it can be done, but still, I’d like to see contemporary authors try.”

Let’s see….. “no contemporary veteran-author has yet written…”, and “no contemporary war novel is…”, and “no one writes novels like The Thin Red Line anymore…”.

Definitive assertions, Peter, and they shall remain true as long as one’s approved-fiction-author reading list must first be certified as “supremely talented” by NYU MFA profs and Phil Klay and Kevin Powers and Ron Capps, and the like.

Don’t bemoan what you aint never gonna discover yourself if you so blinder yourself and are unable to conceptualize that it is more likely that your Jones/Mailer/Shaw/Wouk might just be hiding among the hoi polloi, writing passionately as they did, for storytelling and truth, not for esoteric literary journals and pretentious Illuminati awards.

I offer the first sixty pages in pdf straight from a contemporary war novel (word for word, page for page), proudly NYU MFA-non-certified, right here: https://tattoozooblog.files.wordpress.com/2014/04/tattoo-zoo-sample-pgs1-60.pdf

And then, it’s time I stopped walking a tightrope, stopped playing games; incongruous perhaps for a writer, but I judge a man not for his words but for his actions.

I dunno… Peter’s read virtually everything, or as much of the canon (both general literature and war lit) as any one person could be expected to read. He knows from quality, as my grandma would say.

These lists always have limitations, and no one can account for the yet-unpublished novels out there…. but making such a list in the first place is a challenge, and he took a very informed approach. The whole “M.F. A.” comment seems like baiting, and maybe that’s what you’re going for, but sometimes maybe we should sit back and absorb knowledge from people who’ve put in the time and the study and the work.

Hi Andria, thanks. Another novel I’m being told I should have been more appreciative of is Matterhorn. Truth to tell, I haven’t read it yet, though I love Karl Marlantes’ non-fiction work What It Is It Like to Go to War. If and when I get to it, and feel the need to revise my opinion, I’ll do so. I’m a little bit leery though, based on my reading of recent efforts to write “panoramic” old-style novels on other (non-war) subjects–they usually seem a little creaky for the same reasons that the thick, realist novel fell out of literary fashion in the first place, plus a few more that come from trying to appropriate the mode of an older moment after the moment has passed.

Hey, Paul, easy on the insults, please. I’m reading Tattoo Zoo now and when done will be happy to sing its virtues.

Peter, no intent to insult and offend, but I can understand that both insult and offense would be apparent in my words that come from the frustration, impatience and the barely-subdued rage that, (yes, you are correct), so far, when it comes to the Afghan and Iraq wars, “no contemporary veteran” author of the big storytelling of a Jones is publicly known, never mind heralded. If TZ entertains you and enlightens you and moves you the way it is meant to, then you, clearly in the midst of the veteran-author literary world, might be quite surprised to learn from my experience just how inaccessible and locked down tight that world is to the ragged peasant standing outside the tall castle gates.

Andria is spot-on about the extent of your reading and your knowing “from quality” (though you shy away from negative criticism; understandably, because you strive to promote the reading of war lit rather than to stifle it), which is why perhaps I’ve been waiting and waiting, crossing my fingers on yours to be the respected initial, open and receptive, voice that is excited and passionate to tell the others comfortable and incurious in that world to look over the castle walls, to look below at that fellow standing alone there.