One reason I like books about war written by civilian authors is that I’m interested in what aspects of military experience and combat intrigue them most. Soldiers who write like to explore their reasons for joining, their initiation into the business of killing, their contemplation of mortality, their fraternal feelings with fellow soldiers, their contempt for the chain-of-command and its explanations for why they are fighting, and their alienation from the civilian world unto which they return. Pretty typical, when you think about it, right?

One reason I like books about war written by civilian authors is that I’m interested in what aspects of military experience and combat intrigue them most. Soldiers who write like to explore their reasons for joining, their initiation into the business of killing, their contemplation of mortality, their fraternal feelings with fellow soldiers, their contempt for the chain-of-command and its explanations for why they are fighting, and their alienation from the civilian world unto which they return. Pretty typical, when you think about it, right?

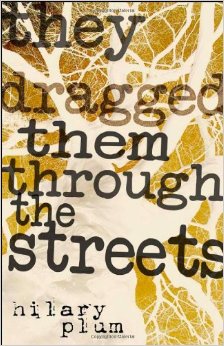

But different things catch the eye of civilian novelists. Hilary Plum, for example, in her 2013 novel They Dragged Them Through the Streets, describes the coping methods of a group of anti-war activists after their leader Zechariah Berkman blows himself up while making a bomb meant for a military recruiting station. The group’s radicalism has been catalyzed by the suicide of the brother of one of its members. Jay, an Iraq vet, has hung himself while struggling with PTSD and alcoholism, and his death inspires his brother Ford and friends Zechariah, Vivienne, Sara, and Ford’s girlfriend “A” to seek violent retribution against the war machinery and the duped public that supports it. The novel, told in alternating short chapters related from the point-of-view of each of the major characters, describes their efforts to understand the allure of revolutionary violence, Zechariah’s charismatic influence and tragic death, their fascination with a war most Americans think little about, and their own tangled feelings about Jay and each other.

Vivienne, the novelist, seems to express perspectives that most closely resemble Plum’s. Or, at least, she is the most articulate about what it means to try to write about war, as when she describes Zechariah:

Dangerous how Z lived, then, for he never slowed. Typing furiously, reading everything, his voice rising as he spoke on the phone. The war the war the war. He commissioned pieces for his magazine and was never satisfied with them. Just chatter, he’d say, waving a hand at the screen, slamming books closed. Waste of time.

Vivienne takes a more meditative approach, though she is also aware that the war saturates her thoughts and writing:

Now I have become a book myself, by which I mean, something whose choices have already been made. What I mean is—the past is lost to us. Its dreamed-up cities, its false trees of words. There’s no way to live among them; touch them and they crumple, or the hand just goes through. The sentences a web stretched over the paths I walked with A, the dew on its strands destroyed by our passing. I am not even that, not even a twist of silk stretching from twig to tree bark. I am a relic, the simple fact of the past…. This is why my novels are not novels of history: they loop and loop. In the end either the feet dangle or the whole slips away free.

While Zechariah’s and Vivienne’s relationship with war is cerebral and textual, the other characters’ ties are more visceral. Sara works as a nurse in a shelter for veterans and the homeless. A, Ford’s girlfriend, begins an affair with a journalist who has worked in Iraq. Ford, of course, bears the biggest burden, not so much A’s treachery, which doesn’t seem to bother him much, but the death of his beloved older brother. Plum’s greatest interest seems to be the collusion of forces that might drive a war opponent to political violence. In retrospect, such an investigation is mostly mute, because political opposition to the war, even in the early days when the invasions of Iraq and Afghanistan were presided over by the big-bad triumvirate of President Busch, Vice-President Cheney, and Secretary of Defense Rumsfeld, was feeble, and in the wars’ later stages, opposition was totally dissipated by feel-goodism for “the troops” and President Obama, as well as the blissed-out national mania for social media. In America, the revolution not only was not televised, it wasn’t even documented by status updates, because it didn’t come close to happening.

Well, better words than bombs, truly, though Zechariah’s belief in print-and-paper journalism seems a little quaint. Why doesn’t he get his thumbs flying on his smartphone?! But I salute Plum for exploring the conditions that might radicalize a dissatisfied citizenry to the point of violence. They Dragged Them Through the Streets resembles greatly Doris Lessing’s The Good Terrorist, a 1985 novel that portrays a similar assortment of privileged white bomb-makers struggling to reconcile murder in the name of politics with middle-class upbringings. As it happens, I read The Good Terrorist in my plywood bunk on FOB Lightning, Paktya province, Afghanistan, in what passed for my downtime during deployment. Grabbed at random from the book exchange in the Morale, Welfare, and Recreation Center, The Good Terrorist induced reveries that had me comparing the political docility—that is to say the civility—of the white West with the rage of our Afghan enemies, who rained rockets and mortars upon our camp and sprinkled the roads we traveled with IEDs. The comparison made me think that Lessing might have rendered her bourgeois revolutionaries in shades more comic or accusatory than respectful. The same charge could be levied against Plum, but that would be wrong. As her character Vivienne’s words remind us, imaginatively portraying a world that didn’t happen helps us understand better the one that did.

RIP Doris Lessing, 2007 Nobel Prize laureate, d. 2013.

Hilary Plum, They Dragged Them Through the Streets. The University of Alabama Press, 2013.